Imported modular houses could help to address NZ’s housing affordability crisis🍋

NZ has experienced some of the largest house price increases in the OECD over the last two decades

Improving housing affordability is a priority for the New Zealand Government. Housing Minister Chris Bishop openly refers to the current situation as a “crisis,” and has stated his intention of “flooding” the market with new dwellings. This is a positive development given that New Zealand has experienced some of the largest house price increases in the OECD over the last two decades, and that rents are taking up a growing proportion of households’ disposable incomes.

The Government has sensibly identified supply-side issues as the primary culprit. Its policy efforts to date have therefore included measures to free up more land, making it easier to intensify housing in existing areas, and removing regulatory barriers. None of these measures are silver bullets, as the Minister has acknowledged, and more needs to be done if house prices and rents are to be brought down further.

I propose an additional policy approach to help to lower housing costs — facilitating the import of modular houses.

For most New Zealanders (at least of a certain age) mention of prefabricated or modular buildings brings images of low-quality school classrooms to mind1.

Modular construction has come a long way

But modular construction techniques have come a long way. Modular dwellings are now of equal or higher quality than conventionally built ones. Internationally, modular construction approaches are disrupting traditional building techniques.

The magnitude of this shift towards modular housing construction should not be underestimated. Nearly one in four building permits for one- and two-family homes in Germany are for prefabricated timber homes.2 Sales in Germany reached €3.49 billion (NZD6.15 billion) in 2021.3

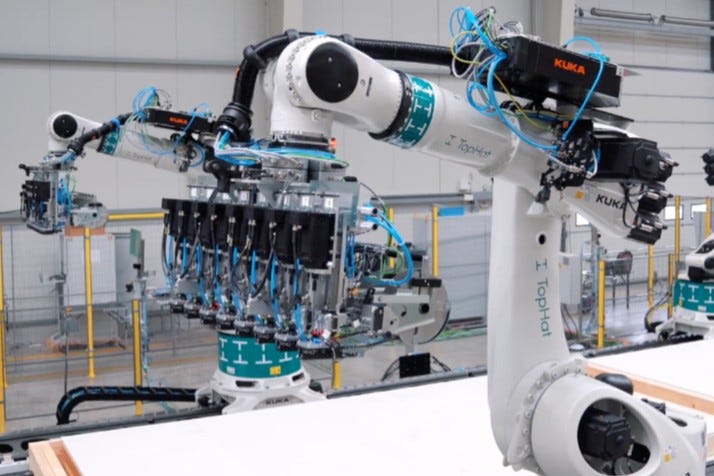

The sector is also increasingly technically sophisticated. The firm TopHat recently completed a new modular construction plant in the UK with robotic and production line processes similar to those in the automotive industry. That factory can produce a new home every hour, and is capable of constructing a habitable house from order to installation in just two to three weeks.4

This international shift towards modular construction has been driven first and foremost by a desire to reduce costs; modularisation provides cost savings of 10-25%.5 Those cost savings are expected to increase further as the sophistication and scale of manufacturing plants continues to improve. Modular houses are not just cheaper; they are also quicker to build, more energy efficient, and more environmentally sustainable.

New Zealand has followed the international trend towards modular construction to some degree. The sector here has grown quickly, both in terms of the number of firms operating in it, and the number of dwellings sold. Some of those firms are also now reasonably large: transportable home manufacturer HouseMe, for example, has sold close to 5,000 modular units.6

It is hard to imagine, however, New Zealand’s domestic modular construction sector ever matching the size and sophistication of that in Europe, or the USA. Slightly over 48,000 new homes were consented for construction in New Zealand in the year ending February 2023. By way of comparison, the single TopHat factory mentioned above can produce 4,000 homes a year.

Could a factory like that be commercially viable in New Zealand? Our small size and physical isolation tend to lead to low levels of productivity in our non-tradeable sectors.7 Perhaps it is inevitable that housing will remain another example of that, leaving us doomed to face high house construction costs forever?

Modular houses are tradeable goods

My answer to that proposition is a clear “no,” but for a reason that may not be immediately obvious. The rise of modern modular construction techniques has had a second key impact; it has transformed modular houses into tradeable goods. Such houses are frequently flat-packed after construction, then shipped to another country for assembly.

So why aren’t such houses being imported into New Zealand? The answer is simple: it is prohibitively expensive and time consuming to secure building consents for such imported dwellings. I cannot find a single example of a consent being issued for an imported house. Indeed, several web forums exist on the topic, with the primary message being “Believe me, you do not want to go down this path”8.

That does not need to be. Other countries have enabled the import of modular dwellings, and New Zealand should too. The previous government took sensible steps to make it easier for locally built modular houses to be consented. Those changes saw local manufacturers able to apply for certification, which once granted meant that modular components they produce are automatically deemed to comply with the NZ Building Code.

That existing solution does not help with importing modular dwellings. However, it does illustrate the path forward. New Zealand already relies heavily on imports for most advanced manufacturing goods such as cars, machinery, and IT equipment. Trade in such goods is facilitated by a largely unseen web of internationally harmonised standards and accrediting bodies. That system already ensures that the Chinese toaster or South Korean car you buy is safe for you to use, and will perform satisfactorily under local conditions.

Other countries have earthquakes too

The common concern raised with this idea is that New Zealand’s environment is different, and that we therefore need bespoke building standards. But is that really true? California and Italy have earthquakes, which is reflected in their building codes. Winter temperatures are colder in much of Europe, so their insulation standards should more than suffice. And heavy rain and high winds are common in northern Europe.

The adequacy of other countries’ building standards for the New Zealand environment needs to be carefully assessed, but their inadequacy should not be assumed. The EU is in the process of moving towards a single building code, and the US largely already has one (in both instances with regional variations).9 If the adequacy of those building standards was confirmed, New Zealand consumers would quickly be able to access an enormous variety and number of modular dwellings.

Unilateral recognition is the way forward

The regulatory approach to allow that would be straightforward: where a modular house has been certified as meeting an international standard that our government has assessed as meeting New Zealand requirements, the dwelling would be deemed to comply with the Building Code, and therefore able to be consented by the relevant council.

This approach would address existing construction-sector challenges around the high cost of materials, labour shortages and supply chain disruptions, with a substantial improvement in the productivity of a vital part of the economy.

Two sensible first steps for the Government would be to:

Undertake an analysis of the equivalence of the requirements of New Zealand’s Building Code against those of the EU and USA, identifying areas where our code has more stringent requirements.

Undertake a review of the approach of other OECD countries, such as the UK and Canada, to ensure that imported modular buildings and building components meet the requirements of their building codes.

By Andrew Sweet

The Ministry of Education used relocatable classrooms through the population-boom period post-World War II. In those years school prefabs made up to 85% of floor space built each year.

Karthik Subramanya, Sharareh Kermanshachi & Behzad Rouhanizadeh (2020). Modular Construction vs. Traditional Construction: Advantages and Limitations: A Comparative Study.

A recent MFAT working paper (Bailey & Ford, 2017) found that firms in tradeable sectors are 59% more productive on average than those in non-tradeable sectors.

See for example: Importing a kit/prefab house from Europe - New Zealand (enz.org)

In the United States, each state adopts a version of the International Building Code (IBC). The IBC is updated every three years, with the latest version known as the “2021 IBC”. Each state has its own code adoption cycle and polices for amending the IBC, resulting in a national base-model code with regional variances.

Thank you for an informative read.

But I can’t find any evidence that the government has done any research for easing the housing situation so Ministers are just turning their various “I think” brain farts into policy.

We have been watching a modular housing project in Northcote fail - while half a dozen tilt-slab apartment blocks have been built, finished and inhabited, the stacked modular 'containers' have stalled for so many months it seems like years. A group of workmen who might have been sent by the Asian manufacturer, is now patching, sealing, plastic wrapping and clambering over the structures with cranes and all get-out. Good on the council for catching the issues. The more successful tilt-slabs were themselves innovative, two or three on stabilised foundations of pine poles, the concrete was patterned and stained to look like timber, sometimes brick facaded with tukutuku patterns, all units seem to be street facing, the ones I have seen are no more than two off a foyer, trees abound, and they are priced at what goes for 'cheap' these days - many Kainga Ora, some privately owned and some private rentals. Either build the modules here, like classier school classes, or don't go this route. Come and see, imported modules in the shipping container style have been a disaster.