As 2022 draws to a close, once again the hype surrounding fully-automated driverless trucking fleets and ubiquitous cross-country journeys in self-driving cars — which according to Elon Musk are always just around the corner — is exposed as one more chimera in the mist. Far from causing mass unemployment for professional drivers, the world is currently facing a driver shortage across all forms of commercial vehicles, from taxis and buses through to road and rail-based trains. Even the aviation sector — long supported by the software-based autopilots — is facing unprecedented human capital deficits.

So 2023 is (again) unlikely to be the year that self-driving cars shake up the economy. But there’s a new kid on the AI block. Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools are moving fast, and are possibly the most significant social and economic development in the field. These tools bring together linguistics and mathematical algorithms to take real-world language input (both spoken and written), process it and make sense of it in ways a computer can understand. The tools can then be used to create a vast array of outputs — both oral and written — in response to input prompts.

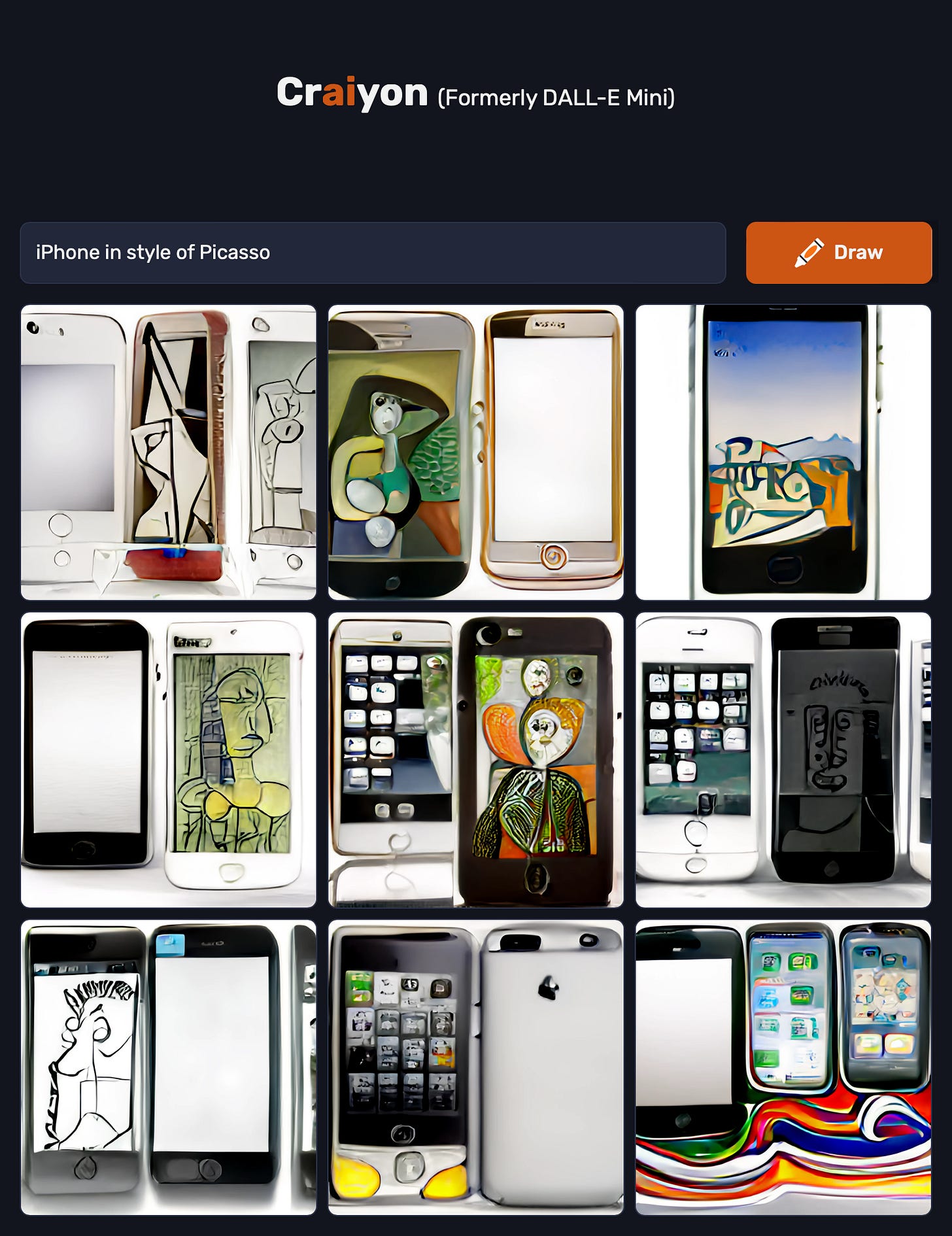

Early iterations of the technology gave us tools such as Google Translate, taking a string of input in one language and giving output in another. Recent variants, such as BERT, GPT-2 and GPT-3, provide far more creative output. These tools are designed to search for and provide answers to direct questions (such as might be asked of a "chat-bot"), complete answers to essay questions, or even poems and songs in whatever style the requester asks. Using similar processes, the algorithms are also able to create visual art outputs.

Defining creativity in the age of AI

My pick is that the hot topic for AI and Machine Learning in 2023 will be the relationship between these new AI tools and creativity. On the one hand, AI artists claim that the works generated are new, novel and attributable to them, because they crafted the prompts that led the software to create the output in question. Kezia Barnett, a New Zealand artist who uses AI, told Stuff that using the tools involves selecting, refining, and editing, and the process has “given me a way to express myself, the freedom to communicate, and brought me a sense of hope and joy.”

My pick is that the hot topic for AI and Machine Learning in 2023 will be the relationship between these new AI tools and creativity

Other artists have raised concerns about their art being used as training material for AI. When entering prompt text, users can specify an artist (e.g. “Picasso”) and see outputs in that style. Polish digital artist Greg Rutkowski commented that his style was so popular it was becoming harder to find his original work online. Other artists have argued that since their art is an input for AI output, AI-generated art is just a more advanced form of plagiarism.

The future of the essay

It’s not just AI images that raise questions about plagiarism, creative inspiration and intellectual property. Similar debates divide academia, where the essay has long dominated as an assessment method. Some educators have opined that if the tools allow a student who would otherwise face limitations in producing outputs to create work which they can be proud of, then that is sufficient to encourage their use by those students at least. Others suggest that there is nothing wrong with using AI-created exemplars to stimulate further creativity, if that assists with giving the student confidence to proceed along that path. One anonymous student, who had been using AI to generate essays told student magazine Canta:

I have the knowledge, I have the lived experience, I’m a good student, I go to all the tutorials and I go to all the lectures and I read everything we have to read but I kind of felt I was being penalised because I don’t write eloquently and I didn’t feel that was right.

On the other hand, I have a problem with accepting, grading and awarding a mark to a student for an essay generated using AI tools.

What do you do if you suspect an essay is AI-generated?

I have little doubt that such essays have already been presented to me for assessment. The tools are very sophisticated, and it is hard to distinguish "fakes" from genuine efforts — though ironically, absence of spelling, punctuation and grammar errors may be a big clue, for some students at least.

How do you feel about AI being used as a prompt for the student to develop and edit?

The issue for me is that I need to assess whether students have demonstrated the core learning objectives of the course, not what the rest of the collective body of AI has been trained to respond with to my question prompt. There is an equity problem when some students answer (imperfectly) using only the (“human”) tools I have shared with them, but others produce a well-structured and technically correct AI-generated essay either lacking the critical thinking features that are core learning objectives of my course (which is easy to identify) or features critical thinking features that are not the student’s work (not easy to identify, but assessable against my objectives).

While human- and AI-generated essays may look equivalent, the “student original” should surely receive a higher grade. But if I cannot tell how each was created, I can’t distribute the rewards appropriately. So the signals that my grades send to society of students’ mastery of the course objectives lacks credibility, posing even more challenges to the bases of educational credentialing.

I am currently contemplating a task where I ask my Decision Modeling students to input my prompt to GPT-3 and then critique the response with reference to the themes and materials covered in the class. It’s a second-best when compared to original critique, as it offers no chance for the most capable students (who don’t usually need electronic assistance anyway) to demonstrate their originality. But it is “fairer”. Ironically, like most AI tools, assigning such tasks serves to reinforce the current corpus of knowledge ,rather than adding to it in and of itself.

A new development in the age-old creativity debate

There’s nothing new about debating to what extent copying is acceptable. As an economy, we make advances by building up on the ideas that went before.1 Creativity can develop in similar ways. Walking through any history of art exhibition allows the viewer to observe, and marvel at, the clear inspiration artists took from one another. The debate, therefore, centres around how much a person copies, and whether attribution is given or appropriate. The addition of AI to the artistic scene, be it words, images or sounds, is just one more development for an existing debate.

Beyond creativity: misinformation and the future of research

These questions are merely scraping the surface of the wide range of issues to be addressed. Should newspapers and websites publish AI-created stories, or attribute them to named journalists? How would we know if they accurately attribute authorship? How can we identify reputable sources, and address new waves of AI-generated misinformation?

In the research field, should AI-led "research papers", which are novel enough to stand up to human peer reviewers, be published in reputable journals? And if so, who is attributed with the research credit — the AI tool or the "researcher" writing the prompts? How should this "research" be valued (or even identified) compared to "blue skies" human research, which even now is aided by the use of search engines for important components such as compiling literature reviews? For example, how should a paper be evaluated if the researcher consigned the literature review to the AI tools, but then conducted and wrote up a novel experiment without electronic assistance?

I, for one, look forward to seeing where this debate proceeds in 2023.

For example, in The Entrepreneurial State, Maria Mazzucato documents how the iPhone was made possible by building on technology developed in the public sector.