Whatever happened to Peak Oil?🍋

A grand idea, fuelled by a misunderstanding of supply and demand...

Humans have no shortage of ideas. While most of these go nowhere, a few ideas do go on to revolutionise the world. In between are many grand ideas that capture the public’s attention and imagination for a time, then fade into obscurity. (Admittedly, some hang around like a bad smell.)

I find it fascinating to re-examine such grand ideas. What was it about a particular idea that led it to gain currency or popularity? Was it based on some kernel of truth? Did the idea’s predictions eventuate, or fall flat? Does it live on, under a different guise? And perhaps more importantly, what can such examination tell us about common misconceptions and analytical errors, which might also be present in the next grand idea to capture the public’s interest?

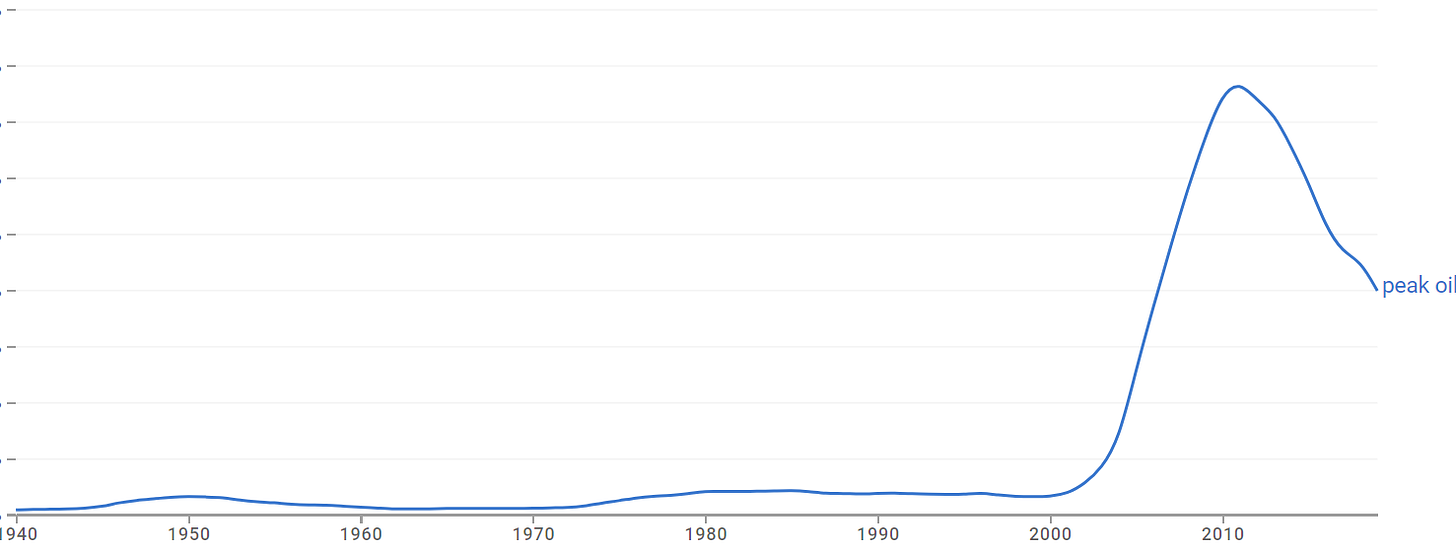

Peak oil is one grand idea that, dare I say, has peaked. According to Google data, public interest in peak oil had a minor peak around 1950, sustained interest in 80s and 90s, and then a substantial peak around 2010. (Interest in New Zealand was very strong circa 2008, coinciding with a period of high petrol prices.)

The good oil on peak oil

Peak oil drew inspiration from the observation that US oil production hit a peak around 1970, beginning a long decline. Given that oil production at scale originated in the US, one might expect it to be the first major oil-producing country to exhaust its supply. Other countries, and the world as a whole, would inevitably follow — with unattractive consequences. According to a 2005 report for the US Department of Energy:

The peaking of world oil production presents the U.S. and the world with an unprecedented risk management problem. As peaking is approached, liquid fuel prices and price volatility will increase dramatically, and, without timely mitigation, the economic, social, and political costs will be unprecedented.1

Important features of the peak oil idea included that the peak was due to physical limits to supply, and that oil prices would increase as scarcity started to bite — and as the exhaustion of cheap-to-extract oil fields forced producers to exploit more costly fields. Physical exhaustion would eventuate at the point when the energy costs of extraction exceeded the energy that could be obtained from extracted oil.

Some inconvenient data

We now know that the 1970 peak in US oil production was a local maxima, one exceeded in the past decade.

Peak oil tells us that scarcity is the primary driver of price and that scarcity is increasing as the global peak of oil production approaches. If so, the following graph, showing the relationship between oil prices and oil consumption over time, should display a strong track from the lower left quadrant towards the upper right.

Such a track is weak, at best. The data fails to fit the grand idea.

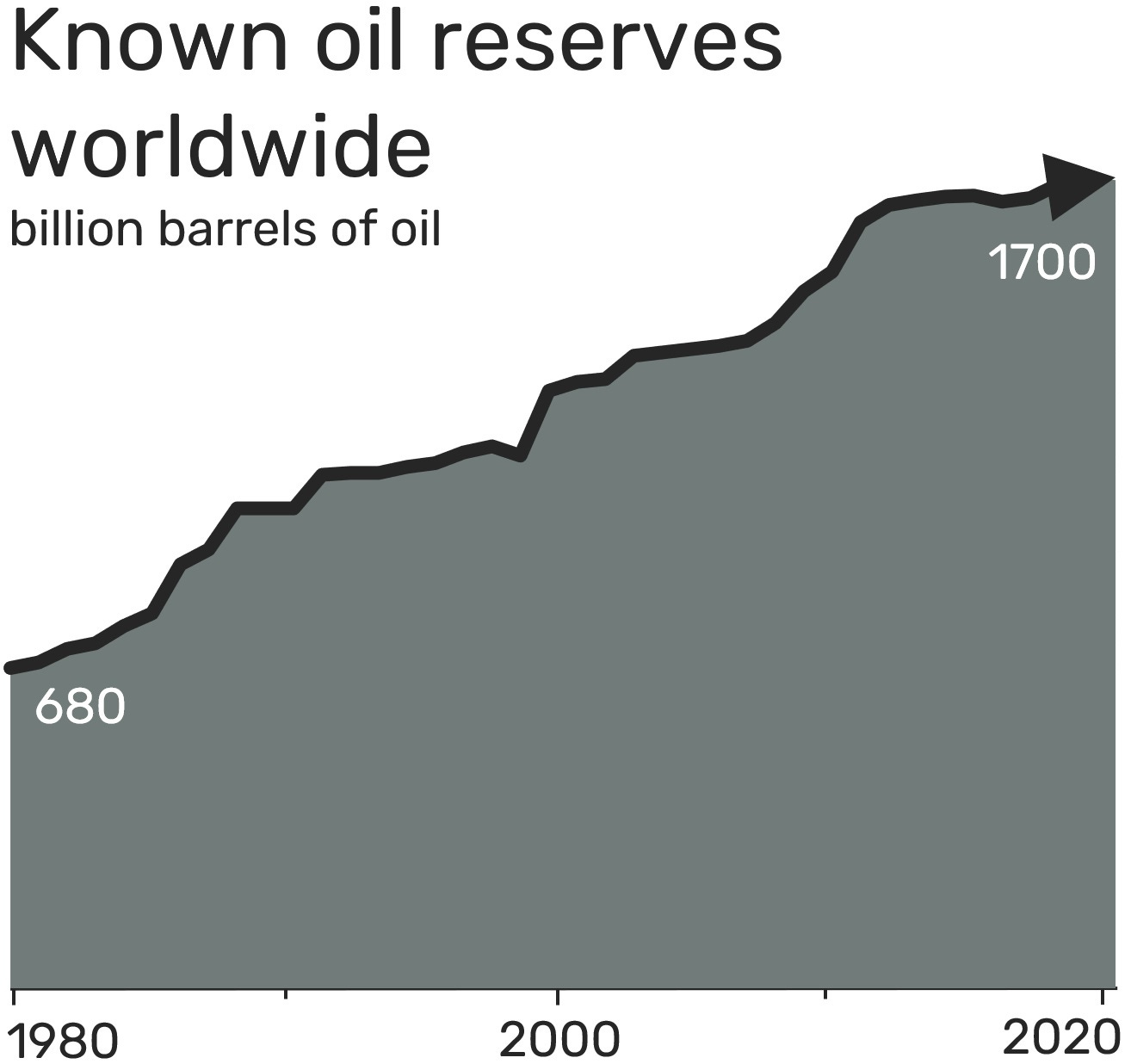

Just how constrained is world oil supply? Known oil reserves have grown over the past 40 years, even as production has risen. If a supply crunch was imminent, then reserves would be falling, not rising.

Some inconvenient theory

Peak oil relies on a very simplistic economic model of a market, focused on scarcity and the costs of supply. The oil market, however, is very dynamic. Factors absent from the peak-oil market model include:

technological improvements, including new survey and extraction methods, and unconventional oil fields;

producer cost savings, including scale and efficiency;

production substitutes, e.g. natural gas, nuclear energy, wind & solar farms;

consumer cost savings, e.g. more efficient vehicles;

consumer substitutes, e.g. EVs, home solar panels;

cartel behaviour, e.g. OPEC;

stockpiling; and

government market interventions, including taxes, subsidies, and regulatory restrictions.

Prices and production levels are the results of the complex interplay between all these factors, together with costs of supply and final demand for energy, transport, and industrial products. Importantly, higher oil prices discourage demand while encouraging substitution, technological innovation, and oil exploration.

What will limit oil production?

Peak oil has its roots in the limits to growth ideas that gained prominence in the 1960s and 70s.2 Limits to growth thinking focused on the depletion of non-renewable resources, holding technology constant in the long run, and assuming that neither producers nor consumers respond to price changes.

Looking back 60 years, one general but very important observation we can make is that resource-supply limits do not appear to be currently binding on human activity, nor likely to become binding in the near future. Pollution limits, however, can be binding.

This generation’s challenge is to restrict greenhouse gas production to within the limits of the Earth’s capacity to absorb them. Rather than wean ourselves off oil before it runs out, we need to leave most of it in the ground, unburnt.

Burning the world's remaining fossil fuel reserves would unleash 3.5 trillion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions—seven times the remaining carbon budget to cap global heating at 1.5C.3

Leaving fossil fuels in the ground will require self-constraint from producers and consumers, regulation by governments, and international cooperation. We can expect the residual value of oil reserves to decline to zero. Contrary to the peak oil idea, this should cause the world price of oil to fall, as producers and countries rush to extract any value they can from assets soon to be stranded in the ground.

Has the world already reached peak oil?

World oil consumption hit a maximum in 2018.

It’s too early to tell whether 2018 will be the long-run peak. If not, I suspect it’s not too far into the future. The peak, when we do reach it, looks to be one enforced by cooperation and regulation to meet a pollution limit, and enabled by supply- and demand-side substitutes. It won’t be forced upon us by supply scarcity.

The grand idea of peak oil turned out to be based on poor data and flawed economics. It did contain a kernel of truth — if you extract any resource faster than it is being created then it has to run out, eventually. But the case for an imminent supply crunch was — and remains — weak.

Why was the grand idea of peak oil so attractive? I suspect many found it added an extra argument and a convenient urgency to causes they already held dear — government action to reduce private vehicle use and greenhouse gas emissions, for example.4 This convenience led them to overlook peak oil’s flaws, or at least not to actively seek them out.

We may, or may not, have reached peak oil. There are lessons to be learnt, regardless.

By Dave Heatley

Rather than wean ourselves off oil before it runs out, we need to leave most of it in the ground, unburnt.

Contrary to the peak oil idea, this should cause the world price of oil to fall, as producers and countries rush to extract any value they can from soon-to-be-stranded-in-the-ground assets

What other grand ideas are worth exploring in Asymmetric Information? Let me know in a comment below, or contribute a post.

Robert L. Hirsch, Roger Bezdek, & Robert Wendling. (2005). Peaking of world oil production: Impacts, mitigation, & risk management.

Donella H. Meadows et al. (1972). The limits to growth.

Galey, Patrick (2022, September 20). Fossil fuel reserves contain 3.5 tn tonnes of CO2: database.

There always seemed to me to be a contradiction between environmentalist’s claims that (a) oil scarcity and high prices were imminent; and (b) increased government regulation was necessary to reduce oil-related greenhouse emissions. Surely (a) would do the heavy lifting, obviating the necessity of (b)?

Interestingly, while on the topic of peaks, it looks like China has hit peak oil demand: https://cleantechnica.com/2023/10/11/chinas-oil-gas-giant-sinopec-says-peak-oil-demand-already-happened-in-china/

I have a book on the topic "Beyond Oil - the view from Hubbert's Peak" by the geologist Kenneth Deffeyes in my bookshelf. When it became clear oil/gas from shale deposits was beginning to have a significant impact on the market, I asked him to come on the RNZ Nights radio show I was then hosting. He never replied. But the story of "Peak Oil" is one of the reasons I am a little skeptical about changes to transport policy based on mitigating climate change: people will pay to keep what doing what they like (driving and flying) and that money will fuel (whoops - bad pun) investment in technology that will allow them to do so (electric vehicles, planes, biofuel etc). For me, investment in public and active transport is more about having transport choice; cars are terribly convenient until we all use them at the same time, and I get sick of being part of the "congestion problem" in a traffic jam, when I would happily take a train/bus if the service was good enough. However, we should perhaps be wary of the story of "peak oil" leading to complacency; for me, the single biggest threat of climate change is what happens if it cuts into the production of a staple food crops: even inflation caused by a drop in grain production could be pretty distabilising, let alone serious famine; how the world handles those potential blips, could be the biggest challenge humanity faces this century. I'm all for doing what we can now to potentially smooth those bumps out.