We need to talk about KiwiRail🍋

Despite billions “invested” by government, its financial performance continues to deteriorate

KiwiRail is a state-owned enterprise, and so by law its principal objective is “to operate as a successful business”.1 Success in the business world means that you provide something that your customers are willing to pay for, at a price for that exceeds your cost of production, leaving something to reward your owners/investors for the resources they have committed. How does KiwiRail measure up against that?

KiwiRail came into existence in July 2008. It now has 16 years of annual reports for us to delve into.2 In those reports, comparisons across time are tricky. KiwiRail’s KPIs seem to change from year-to-year, and the frequent restructures, revaluations and one-off adjustments on its balance sheets and profit-and-loss statements tend to obscure its financial performance.

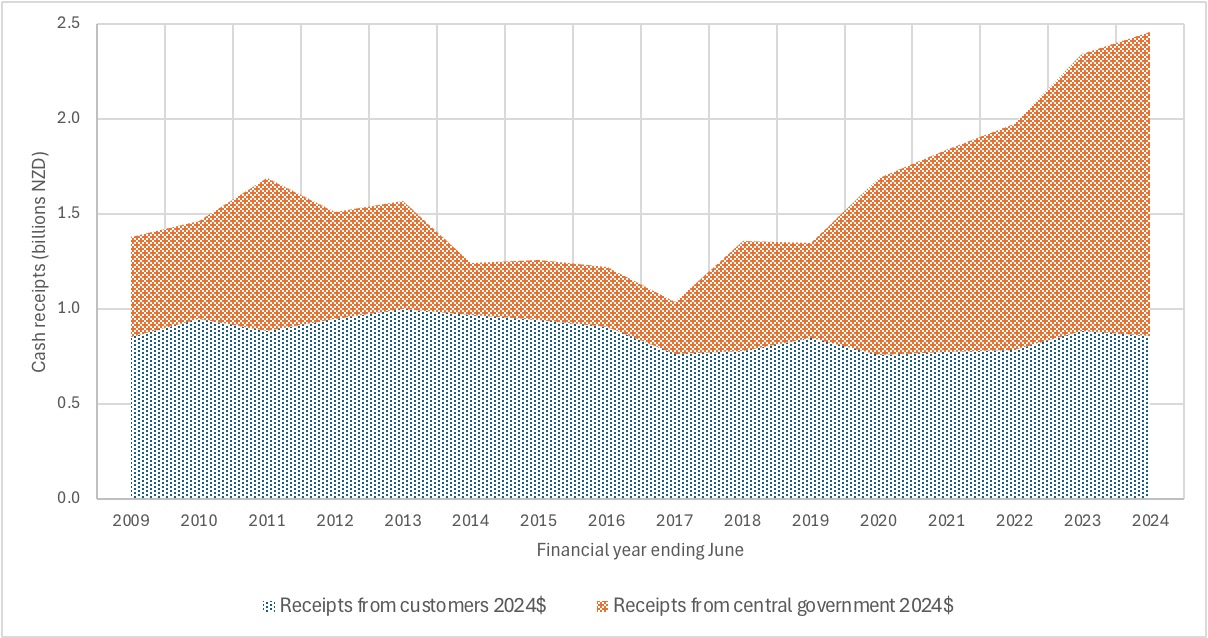

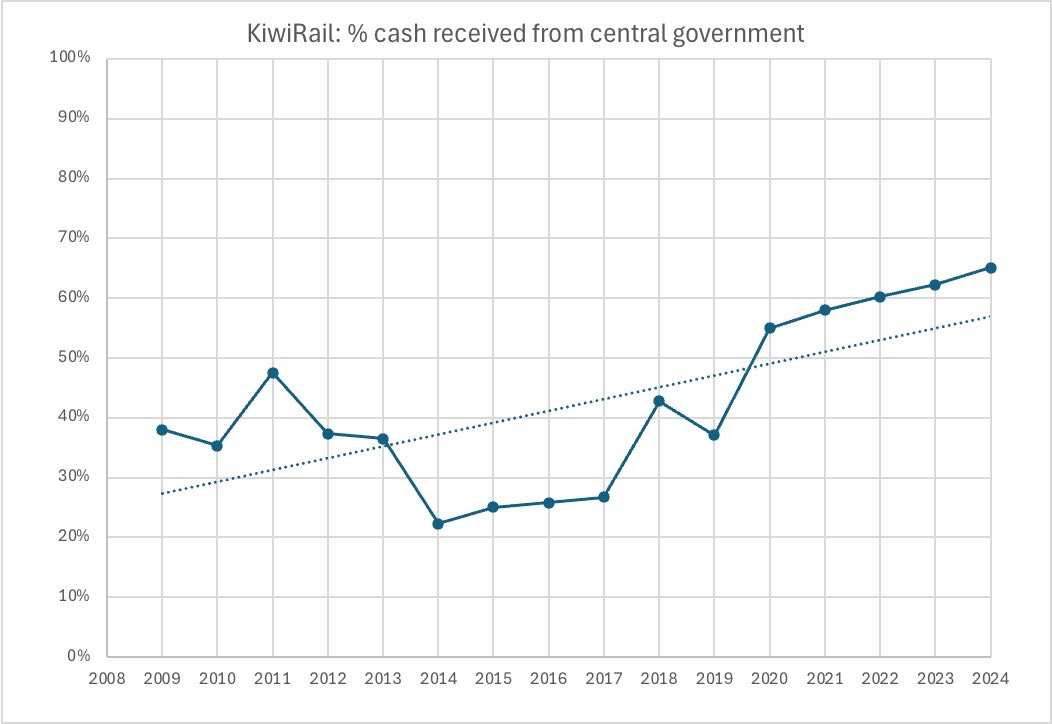

Having tried a few approaches, I think the best way to understand its long-run business performance is through its cash flow statements. In these it is easy to separately identity “revenues from customers” from “revenues from central government”.3

As you can see, receipts from customers have been pretty much flat over those 16 years. Receipts from central government, however, have made an increasing contribution to KiwiRail’s revenue.

Rather than having something left over to rewards its owners/investors, KiwiRail has been a consistent drain on them. Total cash receipts from government have been $11.67bn (in 2024$) — approaching half of all receipts.

KiwiRail’s customers provided just 35% of its income in 2023/24.

To put these figures in context, the $3bn of government funds that went into KiwiRail over the past two years could have paid for the Dunedin Hospital rebuild, which is at risk of being scaled back for affordability reasons.

Who are KiwiRail’s customers?

KiwiRail has three main groups of customers. In order of (revenue) importance, these are:

rail freight customers (moving coal, logs, containers etc.)

Interislander customers (taking vehicles and passengers across Cook Strait)

regional council customers (providing tracks and signaling to support commuter rail services in Auckland and Wellington).4

Independent analysis shows that Interislander is a profitable business for KiwiRail. Interislander’s private-sector competitor, BlueBridge, certainly is. And I have no reason to believe that KiwiRail is not recovering its costs from Auckland Transport and Wellington Regional Council.5 So, the gap between revenues and costs would appear to be primarily attributable to KiwiRail’s freight services.

Revenue from customers is flat

Revenue from customers was $858m in 2023/24, just a smidgin over the $854m (in 2024$) received in 2008/09. But New Zealand’s population has grown 25% since 2008, and the total amount of freight moved in New Zealand has also increased significantly. Flat revenue in a growing market means that KiwiRail’s share of the freight market has been falling over time.

Catch-up investment, to bring KiwiRail back to commercial viability?

KiwiRail and its supporters have long claimed that rail assets were run down prior to 2008, and that a “catch-up investment” in asset renewal was necessary to bring its network up to modern standards, after which market share would expand and KiwiRail would be commercially viable. The KiwiRail Turnaround Plan 2010, for example, envisaged that a $1bn government investment over four years, followed by a $4bn reinvestment of profits over the following six years, would lead to commercial viability. KiwiRail received the $1bn (and more) of government investment, but profits, reinvestment and commercial viability did not follow.

As to the state of rail assets following more than a decade of “catch-up” investment, the New Zealand Rail Plan 2021 gives a sobering assessment:

KiwiRail has been unable to fully fund the level of investment needed to sustain the full national rail freight network. Many core operational assets are at the end of their economic lives and need to be replaced, such as the Interislander ferries, rolling stock and maintenance depots.

Operational restrictions, increased failure rates across the network and unplanned disruptions limit rail’s contribution to the transport network. The full potential for commercial growth in freight and logistics propositions has not been able to be realised.

How long is too long?

A much quoted definition of insanity is “repeating the same mistakes and expecting different results”.6 Successive New Zealand governments have officially accepted arguments that KiwiRail is just one big subsidy cheque away from meeting its principle objective, to operate as a successful business. Sixteen years of financial accounts suggest otherwise.

If KiwiRail’s assets are still in poor condition, and its market share and commercial viability are in a worse state, then what has the government’s continuing investment in KiwiRail actually achieved?

I think it is high time we had a mature national conversation about KiwiRail.

State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986, s.4(1).

The annual reports cover the financial years 2008/09 through to 2023/34. Reports from 2012/13 onwards can be found at KiwiRail annual reports. See our KiwiRail document archive page for reports from earlier years.

While the cashflow statements have a single line item for receipts from customers, receipts from central government are spread across several line items. In some cases I have made judgements as to what does or does not constitute receipts from central government; when making such judgements my main criterion is whether a normal business would have received that payment. The items requiring judgement were relatively low-valued, so different judgements would not materially change the observations in this post.

KiwiRail also run tourist train services, and passenger services for Horizons and Waikato regional councils. These are relatively unimportant sources of revenue within their overall business.

I don’t have any data on which to base this assertion. Economic theory might focus on the fact that both parties (i.e. KiwiRail and the regional council) have substantial assets specific to their relationship. The price paid will be the outcome of a negotiation, in which either party would find it all but impossible to walk away, but might delay agreement or otherwise withhold cooperation if the price offered was untenable. Such a negotiated price will typically end up somewhere between the walk-away prices of the two parties.

Yes, we need to talk about KiwiRail, and recognise it for what it really is. It’s a quasi public service, in SOE drag. The problem with KiwiRail is not KiwiRail itself, but actually how we view it. We need a different perspective.

KiwiRail is an SOE, but only for want of a more appropriate entity form. In 2021, the government recognised this, and asked the Ministry of Transport to review its status. In the Terms of Reference, it stated:

“When considered from a combined above- and below-rail perspective, KiwiRail is not a viable commercial business as it generates only a portion of the cash required to fund its investment in above- and below-rail assets. The Crown’s willingness to meet the funding gap is due, in large part, to the Crown’s desire to purchase wider public benefits associated with rail, such as reduced road congestion and lower emissions.”

Unfortunately, the MoT review produced no change, confirming KiwiRail to be an SOE, despite this being an unsuitable entity form. This was not a good outcome, because it constrains KiwiRail from growing its business, and it leads observers to have inappropriate expectations, as evidenced by Dr Howell’s article. KiwiRail is a square peg in a round hole in this respect.

A look into KiwiRail’s accounts shows that the above-rail operations are usually profitable; it is the maintenance of the rail network, the below-rail operation, that is not profitable. This situation is the norm around the world. The only profitable railway networks are monopolies carrying bulk commodities, where competition with road transport is unrealistic. A good example is the Central Queensland Coal Network, operated by Aurizon. Other railway networks in Australia, owned and operated by State governments for general freight, are not profitable, and are not expected to be so.

Dr Howell asks, in relation to the catch-up investments for asset renewals that successive governments have made since 2009, “how long is too long?” Due mainly to privatisation, New Zealand’s railway was starved of capital for about 20 years (1990 to 2010 approximately). Consequently, much asset renewal was deferred. The problem with such deferral is that it is easy to do, but hard to catch up on. It takes many more years to recover from deferred asset renewals than the number of years of deferral, because of limitations in financing, resourcing, and getting access to otherwise operational tracks. For this reason, it will probably take another 20 years to complete the catch-up work, or longer if the current government continues to withhold funding.

Governments need to fund the construction and maintenance of both highways and railways for “NZ Inc” to function well. Therefore, the rail network should be seen as a national asset, complementary to the highway network. KiwiRail does the heavy lifting for “NZ Inc”, moving up to 18 million tonnes of freight per year, of exported and imported bulk coal, export logs and pulp, all of Fonterra’s exports, and other import/export containers.

Domestic freight is a relatively small proportion of KiwiRail’s traffic task. It is constrained in attracting more non-bulk freight because it is forced to play on an uneven playing field, due to the highway network not being structured as an SOE. The recovery from users, of the costs of providing and maintaining highways, is grossly inadequate, largely due to the political influence of the trucking industry.

Freight trains are much more labour-efficient and fuel-efficient than trucks, but the difference in the costs of access to the ‘way’ is a critical element that creates a serious distortion in the market. The government needs to adjust its land transport policy settings for KiwiRail to thrive.

Surely the billions that have been invested were provided by taxpayers? The term "government investment" always seems to me to be rather misleading.