I delivered a short opening address to the NZ Initiative’s The Future of Our Universities symposium in Wellington on 15 May. I aimed to set the scene for the day’s deliberations by being a bit provocative. I thought I would share my speaking notes and slides with AI readers.1

We expect too much from universities

We expect universities to be at the forefront of innovation and social change, yet to embody traditions dating back centuries.

We want universities to challenge and extend our youth – supporting them to take their place as adults in a sometimes ugly world – yet to protect those youth from that same ugliness.

We ask that the credentials doled out by universities identify and elevate the best amongst us, but also that they are within reach of us all, whatever our backgrounds, underlying abilities, dedication and application.

There will be plenty of discussion about these tensions today.

To kick things off, I’d like to cover a further tension: we expect universities to be at the forefront of innovation in technology and business models, yet we constrain their ability to experiment and innovate.

Universities are in the information business

Universities are ultimately in the information business – they generate, curate, verify and certify information. And the once rock-solid business models of other information industries are in tatters – think of newspapers and free-to-air television. There is no reason to think that the university business model is immune from technological disruption.

Universities once had a monopoly on knowledge and issuing higher credentials. Moreover, individual universities had a near monopoly over those in their geographical catchments.

The world has changed. Physical travel has become cheap, which has increased competition in input markets (academics), and in output markets (students). And virtual travel is even cheaper.

Universities have lost their information gatekeeper role. The role of the “expert” has become more contested and arguably degraded. The democratisation of publishing – while not without problems – means that information can no longer be hoarded. And research, even so-called “basic” research, is conducted by a wide range of public and private organisations across the world.

Universities are left with a near monopoly on issuing degrees. But degrees have become less valuable over time: As the degree-holding proportion of the population increases, degrees lose their reliability as a signal of the abilities of their holder relative to the population mean.

Nowadays, around 40% of New Zealanders have a Bachelors by age 35, up from fewer than 10% in the early 1990s.

In most countries, universities retain a near monopoly on government subsidies for tertiary education.2 Somewhat perversely, this make them more fragile than they would be otherwise, as subsidies have the effect of disconnecting prices from costs, and insulating institutions from the consequences of their business choices.

These problems are global. No one can say with any confidence what the solutions are.

NZ’s tertiary funding model makes for a fragile business model

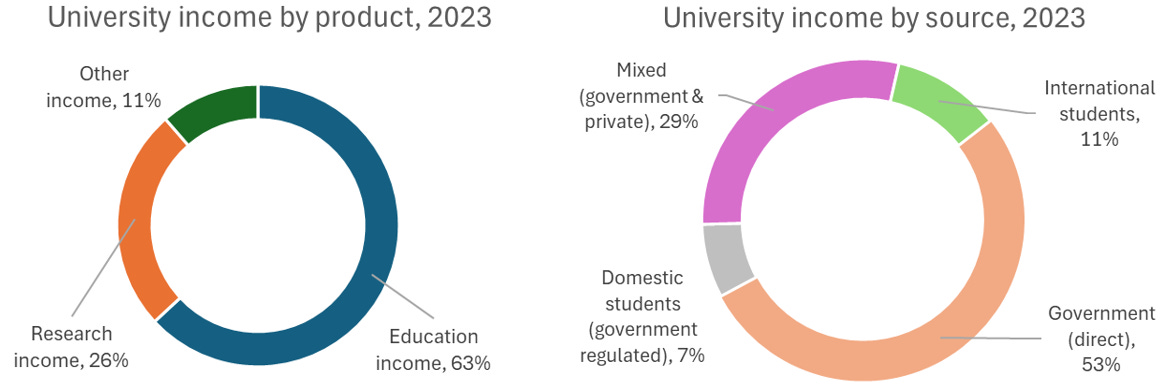

New Zealand’s universities are businesses. Their combined annual income is nearly five billion dollars. If they were a company, it would be among the top five on the NZX. Like all businesses, in the long run they have to cover their costs, or close up shop.

Where does the five billion dollars come from? At least 60% comes from the government directly, or is payment for services whose price, quantity and quality is specified by government.3

And government is a significant indirect source of much of the remainder. The apparent exception – international student fees – are not regulated by government. However, the quantity of places offered onshore is limited by student visas issued by government.

Businesses survive by being responsive to their customers. For New Zealand universities, government is the customer.4

Our universities are particularly fragile, because their products and production technologies are too homogenous, and their ability to experiment is too tightly constrained.

New Zealand universities face short-run revenue shortfalls, due to Covid-era restrictions on international students, and a drop in domestic student demand attributable to a buoyant labour market.

A normal business would respond to revenue shortfalls in many ways, including innovating their product offerings and modifying prices. But such options are not available to New Zealand universities. They cannot, for example, introduce a new course without the permission of their competitors.5 And even with that permission, they have little flexibility over pricing, as new course fees must be set with reference to those of similar existing courses.

The Government has exacerbated short-run problems by constraining domestic student fee prices to below the rate of inflation.6

Short-run revenue shortfalls can be papered over by increasing government subsidies (directly, or via allowing increases to student fees, which are subsidised through the Student Loan Scheme). But that could just delay and compound the underlying problems. The subsidies implicit in government ownership, for example, is likely helping TVNZ 1 to survive beyond its use-by date.

Business models come and go, and businesses that fail to adapt to changing circumstances can die. There was a time when the newspaper, the television station, and Encyclopaedia Britannica seemed permanent fixtures. Universities are in the information industry and thus not immune from technological disruption.

MOOCs were a fizzer, but the next challenge may not be

I acknowledge that, like Mark Twain, universities have cause to comment that the rumours of their death have been greatly exaggerated. For example, universities were largely untouched by MOOCs – massive open online courses.

Looking back, the MOOC only provided one part of the tertiary education bundle:, human capital development. The internet has a trust problem, and MOOCs failed to provide adequate credentialing – reliable certification that person X has gained the learning, whereas person Y has not. But that’s a solvable problem, technologically and socially.

We may come to regard MOOCs as we now do Craigslist and AltaVista – early prototypes of the eBays and Googles that brought down the business models of newspapers and others.

I can’t say what the new business model for universities should be, nor even if a viable model exists in which the university is still recognisable. What I can say is that we’re unlikely to find those new models without an open mind, and the flexibility to experiment and innovate.

By Dave Heatley

New Zealand’s universities are particularly fragile, because their products and production technologies are too homogenous, and their ability to experiment is too tightly constrained.

My observations draw heavily on two NZ Productivity Commission inquiry reports: New models of tertiary education and Technological change and the future of work. (Disclosure: I worked on both these inquiries.) I also drew on my post (with Bronwyn Howell) Price regulation & university failure🍋. I would also like to thank Judy Kavanagh and Amy Russell for helpful input, and Luke Howard at the Tertiary Education Commission for prompt answers to my data queries.

In New Zealand, polytechs, wānanga, and the once and future ITOs all also get sizeable subsidies from government.

“The tertiary education system is controlled by a series of prescriptive regulatory and funding rules that dictate the nature, price, quality, volume and location of much delivery. These controls have extended over time as a result of different financial, quality and political risks. Together they constrain the ability of providers to innovate, drive homogeneity in provision, and limit the flexibility and responsiveness of the system as a whole.” — New Zealand Productivity Commission (2017), p.3.

Most government funding is attached to student enrolments. Where the interests of students and government diverge, university decisions might be influenced more by what will attract students than what will achieve the government's goals. Government isn't good at directly purchasing what it wants — it's more like the parent who sends their kid to the supermarket with an underspecified shopping list.

The Committee on University Academic Programmes (CUAP) approves qualifications offered by NZ universities. CUAP’s membership is made up of a representative from each university (usually at Deputy Vice-Chancellor Academic level), a chair (a Vice-Chancellor), a deputy chair, and a student representative. CUAP conducts a peer review process on all new qualifications or significant changes to existing qualifications.

The Government’s reluctance to allow student fee increases is driven by the cost to government of the student loan scheme. Each dollar borrowed by a student to pay for their student fees costs the government around 50¢.