Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, a giant in both psychology and economics, died in March this year. Obituary writers have done a fine job of documenting his life and work.1 Rather than duplicating those efforts, I would like to share the central insights that I gained from his work, and discuss what we can, or should, conclude from his legacy.

Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow, introduced and explained two ideas to a popular audience:

cognitive biases:, causing human decision making to vary in systematic ways from the optimal or “rational” judgement; and

two systems in the mind: System 1 using heuristics to make quick-and-dirty decisions, and System 2 using deliberation and analysis to produce slower but more reliable ones.

These ideas each have deep implications for economics. They also interact in interesting ways, which I explore in this post.

Cognitive biases meet Homo economicus

Many cognitive biases were discovered and exploited by marketers a time ago. Think of 99¢ pricing, “closing down” sales, and undue emphasis on cost saved rather than price paid. Psychologists and economists, while late to the party, have done a thorough job of documenting these and discovering further ones.

Combined with ways to mitigate or take advantage of their consequences, cognitive biases form the core of behavioural economics. These biases are dramatic enough — at least in experimental contexts — for some to claim they invalidate much, if not most, of standard economics. According to Sendhil Mullainathan and Richard Thaler, for example:

The standard economic model of human behavior includes three unrealistic traits—unbounded rationality, unbounded willpower, and unbounded selfishness—all of which behavioral economics modifies.

The strongest version of this claim relies on a strawman: Homo economicus, or economic man, in which humans are consistently rational and narrowly self-interested agents who take optimal decisions to maximise their own utility. Further, it is claimed that this model of an agent is deeply embedded in the thinking of economists and in the models they use, and thus the conclusions they draw about the real world.

In the non-strawman version, caring about others’ utility can form an important part of one’s own utility function, negating the moral judgement inherent in “narrowly self-interested.” Further, bounded rationality — a concept dating to Herbert Simon in the 1950s — recognises that the quality of decisions is limited by the costs of collecting additional data to inform them. Add to that uncertainty about future states and preferences, including the difficulty of knowing what is best for one’s own long-term physical and mental health, and a more realistic picture of “optimal decisions” appears.

While it is clear from the work of Kahneman and others that cognitive biases affect individuals’ decisions, the conclusions that can be drawn are less clear. How important these biases are for collective decisions? For aggregate behaviour? And for decision where there is a lot at stake? Kahneman’s two systems of mind sheds light, I think, on the latter question.

Two systems, one mind

Our species name Homo sapiens loosely translates as the thinking ape. So, I think, Kahneman’s two systems model invites an evolutionary explanation.

There are evolutionary advantages to being able to decide quickly using simple rules (“heuristics”). Is that a snake in the grass? The best survival strategy is to jump immediately. You can cogitate later over whether it was venomous or not.

However, there are also survival benefits to thinking deeply. Not all snakes are venomous, for example. Non-venomous snakes, reliably identified and easily caught, might be a valuable food source.

Reaction time aside, thinking deeply comes with a further downside. It imposes a high metabolic cost on its host. Brain work, as we all know, can be as tiring as the physical sort. And food has been scarce for almost all of our species’ history.

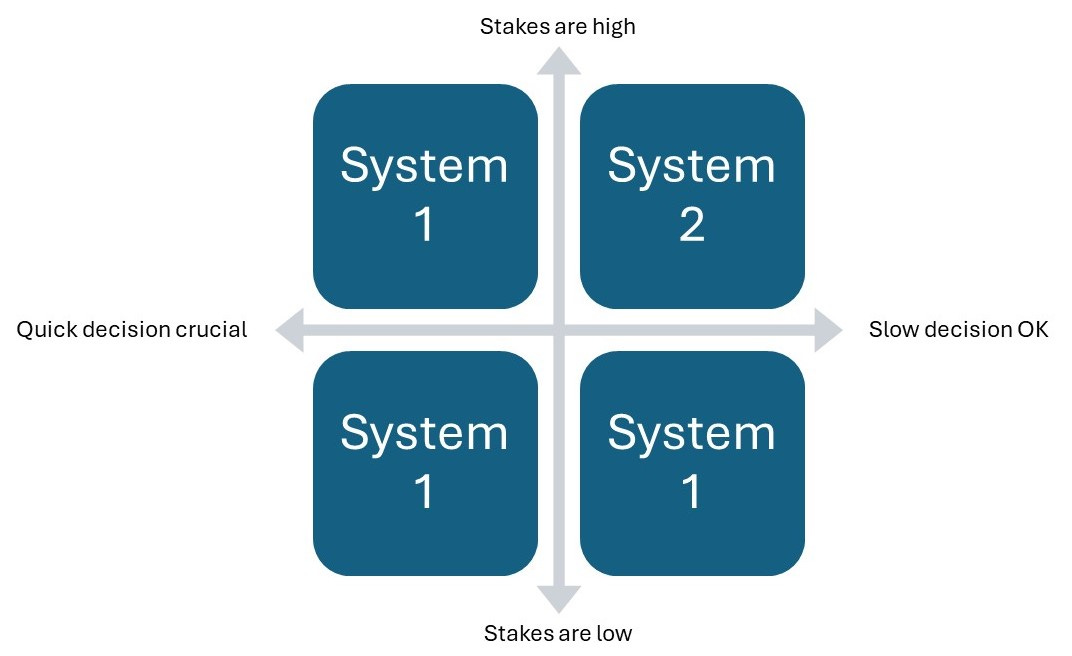

Having two systems and being able to switch between them has evolutionary advantages for humans. But invoking System 2 only makes sense when a slow decision is OK, and the stakes are high (i.e. the consequences of a poor decision are significant). Other times, System 1 is the fast, low-cost and good-enough alternative.

Does System 2 overcome cognitive biases?

System 2 is capable of questioning assumptions, statistical reasoning, and knowing when to seek further information. But it’s not independent of System 1. Even if we think that we are being rational in our decisions, our System 1 beliefs and heuristics still drive many choices. I think it’s fair to say that System 2 gives us the opportunity to overcome our cognitive biases, but by no means guarantees that we do.

When we know something is high stakes, and doesn’t require an instant decision, then we are likely to invoke System 2. Cognitive biases affecting low-stakes decisions are interesting, but largely irrelevant personally and economically.

A cognitive bias with consequences is an opportunity

Cognitive biases, rather than being the death knell of economics, create opportunities. And such opportunities are the bread and butter of economics.

Do cognitive biases mean that a seller can’t realise the full value of a product, or a that a buyer can’t see that value? Then there is an opportunity for arbitrage — a third party who buys low and resells high. Or for intermediation — an organisation connecting buyers and sellers and de-risking transactions for both. Or for institutions — norms and social controls that regulate behaviours. And for regulatory intervention — laws and rules enforced by the state.

To take one example: For most of us, buying or selling a house is the transaction with high financial stakes. Making or accepting a price offer is not something we should do on a System 1 whim. But we buy and sell housing infrequently, so our System 2 is scarcely better informed.

To deal with this, society wraps a lot around housing transactions. Sellers, and some buyers, appoint agents. Regulatory systems constrain the behaviour of these agents. By convention and law, transactions are slowed down. We consult with friends and family, and check our expectations against comparable properties online. Bankers, lawyers, and mortgage brokers offer a similar price check, reducing the likelihood of us under-selling or over-paying.

While some believe that the existence of cognitive biases somehow invalidates economics, I disagree. Daniel Kahneman, and the behavioural economics he bequeathed us, did not diminish economics. On the contrary, he extended and enriched it.

By Dave Heatley

Thank you for your thoughts, Dave. Kahneman’s (and Tversky’s) contributions to economics and decision making theory were transformational, and is fitting that “Thinking, Fast and Slow” is on its way to becoming the best-selling economics book ever. It is a joy to teach with; I am surprised more universities don’t offer a course on decision making theory using this book as a basis, for it is hard to believe there could be a more useful skill in life than learning how to improve decision making in various circumstances. I wish I had read it forty years ago - life would have been quite different. Their 1979 paper on prospect theory must rank as one of the most skillfully designed papers ever as well, combining and extending simple experiments in different ways to convincingly reveal how the way people make decisions is quite different from the traditional understanding espoused by Bernoulli and Morganstern-Von Neumann. It is a paper of pure beauty.

In 2013 Barberis wrote a review for the Journal of Economic Perspectives wondering why it had taken so long for prospect theory to make a bigger splash in many fields of economics other than finance, especially macroeconomics. However, it seems that the profession is starting to make progress. The work of Benabou and Tirole examining motivated thinking suggests that in addition to being “wired” in a manner that often leads to poor decisions, we also selectively ignore information that brings bad news that may threaten our core beliefs about who we are, what we want to achieve, and what we stand for. In a political setting it leads to pandering politicians offering soothing solutions, with occasional bursts of reform activity when things finally get too bad to ignore. In a group or corporate setting, this can lead to group think with occasional costly corporate disasters. So, while corporations often adopt rules that help as avoid bad decision making (eg about taking risky bets on financial markets when someone has lost money), they also can adopt procedures that lead to disaster because no-one wants to question the decisions people are making (and those people that do are excluded). This is fascinating work that seems to directly follow but extend Kahneman’s insights.

It is often said that in New Zealand large policy decisions are made in haste after 12 months intensive work, and then aggressively defended at leisure for 30 years. I am sure you can come up with some examples! Maybe finding a way to develop institutional processes that enable greater recognition of Kahneman's work about the way policy is developed and defended would be a good memorial project.

Andrew Coleman

Ngā mihi nui! Either this is a big coincidence or you heard Cass Sunstein's guest lecture for The Treasury. Will you share your thoughts on Tversky next? 🙏