The many prices of carbon🍋

Have we failed to properly value emissions? Are subsidies justified?

Welcome to 2024! The last Asymmetric Information post for 2023 Is a rail link between North & South Islands really "essential"? generated much interest and lots of feedback and questions. My apologies if I haven’t replied to you in person.

My rail link post emphasised that prices matter when it comes to climate policy:

Those who are serious about climate change know that relentless pursuit of the cheapest options for greenhouse emissions abatement, alongside rejection of expensive ones, offers the best outcome for NZ, and the planet.

More than one reader noted the discrepancy between the social cost of carbon (SC-CO2) and the market price for carbon emissions determined by New Zealand’s emissions trading scheme (ETS), and offered this as justification for subsidies of rail-related emissions-reducing activities. Christina Hood, for example, posted on LinkedIn:

Our ETS price is nowhere near the social cost of carbon (eg US govt uses US$200/t in policy decisions, UK govt uses GBP250/t, and commercial discount rates don’t reflect the social value of emissions reductions. What looks like a “subsidy” is sometimes compensating for our failure to properly value emissions reductions.

Alongside the ETS price and the SC-CO2 sits a third measure — the shadow price of carbon (SPC). Why so many prices for carbon? And is there a “failure to properly value emissions reductions” in New Zealand such that “compensation”, in the form of government subsidies, is warranted to incentivise desirable activities? Alternatively, is there a risk of poor policy decisions if analysts use the wrong price for the right purpose? Let’s investigate.

What is the social cost of carbon?

SC-CO2 is the estimated cost of global damage from one additional tonne of carbon in the atmosphere.1 Equivalently, it is an estimate of the climate-related benefit of any action taken to reduce a tonne of carbon emissions.

Calculating SC-CO2 is difficult. It is highly dependent on assumptions, typically leading to varying estimates, each with a wide range of uncertainty. Fortunately, many smart people have worked on this question. To quote Rennert et al. (2022), writing in Nature:

Our preferred mean SC-CO2 estimate is $185 per tonne of CO2 ($44–$413 per tCO2: 5%–95% range, 2020 US dollars) at a near-term risk-free discount rate of 2%, a value 3.6 times higher than the US government’s current value of $51 per tCO2.

I’ll put variation and uncertainty aside for the purposes of this post, and use the Rennert et al. point estimate of $185. This is roughly $350 in 2024 NZ dollars.

What is more important here is how to interpret and use SC-CO2 in policy decisions. $350 is not a target for what other prices should be. Rather, it is an upper limit, that is, the most society should be willing to pay to avoid a tonne of carbon emissions.

Activities that reduce emissions have social costs too. If SC-CO2 is $350, a carbon-reducing activity that costs $100 would generates a net social benefit of $250, while one that cost $600 would generate a net social benefit of negative $250. The latter should not proceed.

The social cost of carbon defines an upper limit — the most society should be willing to pay to avoid a tonne of carbon emissions

One implication is that if all options to reduce carbon emissions cost more than SC-CO2, then society would be better off accepting global damage than reducing carbon emissions. Fortunately, the world is not in that dismal situation.

What is the market price of carbon?

The market price of carbon is what emerges from the interaction of buyers and sellers in a managed carbon market. In 2023, 23% of global greenhouse gas emissions were covered by 73 such markets worldwide, up from 7% a decade earlier. New Zealand implemented one of the earliest emissions trading schemes; today it has one of the most comprehensive.2 (The NZ ETS still has some holes, but I’ll assume those away in the interests of keeping this post readable.)

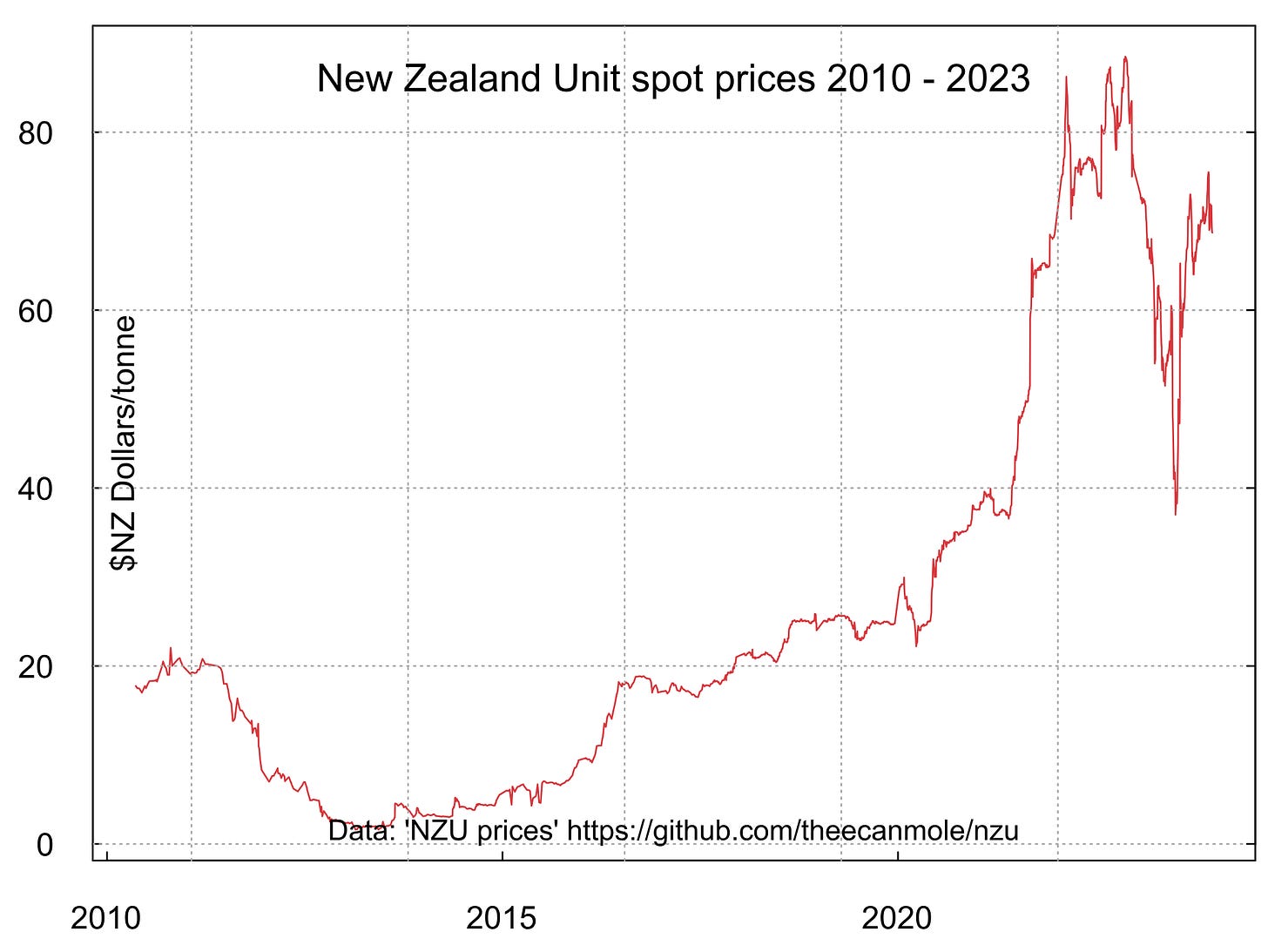

The current NZ ETS spot price is $72. (Technically, it’s the price of one New Zealand Unit or NZU, which accounts for one tonne of emissions). NZUs have tended to trade between $60 and $80 over the past couple of years. By contrast, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme price is around €80 or NZ$140.

The ETS price is best understood as what, according to people with their own money at stake, is the marginal cost of reducing carbon emissions, given current and expected supply of emissions reductions activities, demand for emissions, and scarcity of supply of new units issued by government.

The ETS incentivises those who can reduce carbon emissions at a cost cheaper than the ETS price, as they can make a private return from doing so. Those with carbon-reducing activities costing more than the current ETS price are incentivised to wait — those activities may become profitable should ETS prices rise in the future.

ETS prices also reflect people’s expectations of future carbon prices. For those who believe the current NZU price is low relative to its likely future price, a buy-and-hold strategy for NZU could be profitable. Those who believe the opposite can short sell. Similarly, those with a future obligation payable in NZUs — the case for many plantation forest owners — can buy and hold NZUs to lock in today’s prices, rather than risk higher prices when those obligations mature.

Under NZ legislation, as amended in 2019, supply of new units is constrained within limits compatible with meeting NZ’s Paris commitment to reduce the country’s net emissions to zero by 2050. So, we know that new units will become scarcer over time. That information is helpful but not sufficient to predict the ETS price path. To do that we also need to predict the cost and availability of emissions-reducing activities, the demand for emission-generating activities at various price points, and how those will evolve over time. Not to mention any changes to government policies, including the possible adoption of more stringent commitments.

What is the shadow price of carbon?

I see the shadow price of carbon (SPC) as an estimate of the long-run average cost per tonne of meeting emissions commitments. This should be different from the ETS price, which reflects the short-run marginal cost.

Estimating the SPC, like the SC-CO2, is difficult. According to NZ Treasury, it involves:

making judgements about political economy (government choices on levers and who bears costs), future technologies that may or may not reduce abatement costs, the best mix of low cost abatement (e.g. energy efficiency) vs. higher-cost actions to reduce emissions long term (e.g. R & D), and the nature of international trading arrangements and prices.3

NZ Treasury currently publishes nine values for the SPC, ranging from $121 to $1156. I’ll pick $181 for this post, being the 2024 value for “Shadow Emissions Value CO2 - central price path (Present – 2030)”.4

The SPC is helpful for valuing carbon in very large projects, specifically ones large enough to potentially shift the ETS price, and for projects whose emissions and/or emission abatements are well into the future. The current ETS price may not be a good guide for valuing such projects. The Treasury have done the hard work of integrating available information to arrive at an estimate of where the ETS price might end up. And having one SPC improves consistency between projects within and across government agencies.

The SPC is less useful for small projects, or for ones in the near future. Why would private or public interests purchase carbon abatement at $181 when they could buy the same thing on the ETS market for $72? That would just be wasting resources.

(As a side note, current Treasury guidance recommends using the SPC for carbon co-benefits in cost-benefit analyses. Co-benefits are benefits that are incidental to the purpose of a project. Other guidance recommends using the social cost, i.e. SC-CO2. Valuing carbon co-benefits using the SPC or SC-CO2 distorts decision-making in favour of more expensive options for carbon reduction. I call the practice of using inflated prices for co-benefits the co-benefit fallacy. The correct practice is to use the lowest available cost of abatement, which, for many projects, is the ETS price.)

Enter the carbon abatement schedule

The carbon abatement schedule is a powerful concept. It collects all opportunities to abate carbon emissions, then plots them by the size of the opportunity (Y axis) and the cost of abatement (X axis).

For any given total quantity of carbon abatement desired, the cheapest (lowest social cost) of achieving that total is to start with the opportunities at the left (lowest cost) side, and work towards the right side, stopping when the desired total is reached.5

I’ve added our carbon reference prices to the schedule. At the left are activities worth doing even with a carbon price of zero — these are coloured black. People gain private benefits from these activities. Examples include substituting LED bulbs for incandescent globes — in most situations electricity savings quickly outweigh the extra cost of the bulbs.

A positive ETS price creates private benefits for those activities coloured yellow (and even larger benefits for black activities). The ETS price is sufficient to incentivise these activities; further government policy action is wasteful, in the sense that they will happen without that action.6

Between the ETS price and the SPC are activities that have a net social benefit, but are not privately profitable at the current ETS price. These activities are coloured green. The ETS price is dynamic, so it should drift upwards to include more green activities should yellow ones start to exhaust. (Similarly, the ETS price will move downwards in response to improvements in carbon-reducing technologies such as wind turbines.)

Between the SPC and the SC-CO2 are activities that offer a social benefit, but are more costly than necessary to achieve the emissions commitment implicit in the SPC (coloured orange). They are best avoided unless all black, yellow and green activities are exhausted and emission reduction targets are not yet reached.

Above the SC-CO2 are the red activities. There is no case for pursuing these even if all other activities are exhausted, as they squander social resources. We are collectively better off not meeting emission reduction targets than pursuing these activities.

Within each of the coloured categories above, it is better to pursue activities with lower costs (towards the left) over ones with higher costs (towards the right). A lower cost increases the net private and/or social benefit created.

One price or many?

I’ve given you three reference prices for carbon: social cost $350, shadow price $181, and market price $72. Each of them is right, when used for the purpose it was designed for. And each is wrong, if applied incorrectly.

To go back to the question posed above: is there a failure to properly value emissions reductions? My answer is that there is no one proper value, no “one price to rule them all”, because the different prices have different purposes.

An ETS price lower than the social cost of carbon is desirable, not an indication of public policy failure. The opposite is unthinkably bad — it would indicate no opportunities to reduce emissions that are not, in themselves, more costly than the damage caused by the emissions.

The social cost of carbon tells us a price above which no carbon-reducing activity should be pursued. A lower ETS price is an indicator of untapped opportunities with net social benefits.

Subsidies for projects that offer carbon benefits

How to best think about a subsidy for a project that offers carbon benefits? Think of subsidies as purchases. Framing it that way:

Work out what is being purchased, and the price per unit.

Place the project on the abatement schedule. Where does it sit relative to the reference prices? Will people do it anyway, seeking private benefits? Does the project offer positive, or negative, net social benefits?

Always ask whether the same benefits could be gained at a lower cost with a different project or type of subsidy. If so, pursue that instead. Saving social cost is, after all, a social benefit.

To get back to the question posed at the beginning of this post, a subsidy can indeed be “compensation” for a failure to properly value emissions reductions. But not every such failure deserves a subsidy.

A subsidy is not automatically worthwhile because a “good” thing is being purchased. Throwing subsidies at good things creates a scatter of activities peppered across the abatement schedule, some with net benefits and others with net costs. The strongest case for public subsidies is for those projects offering emissions reduction at a unit cost a little above the ETS price; the case weakens as the unit cost rises.7

Effective policy needs transparency of purpose, rigorous determination of costs and benefits, and clear reference points. The many prices of carbon — properly interpreted — give us those reference points.

By Dave Heatley

A subsidy is not automatically worthwhile because a “good” thing is being purchased — it might just be squandering societal resources.

For a technical explanation of the co-benefit fallacy, and more on using the wrong price for the right purpose in cost-benefit analyses, see the paper White hat CBA hacking, which I co-wrote with Bronwyn Howell and presented at the 2023 NZAE conference.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is only one of the greenhouse gases for which anthropocentric emissions are a concern. I use “carbon” rather loosely in this post as a shorthand for a tonne of carbon-dioxide-equivalent, also known as CO2-e. For any quantity and type of greenhouse gas, CO2-e signifies the amount of CO2 that would have the equivalent global warming impact.

For more information about the NZ ETS, see Environment Protection Agency or Ministry for the Environment.

NZ Treasury (2020). Shadow pricing and climate change [Slides].

NZ Treasury (2023). CBAx Spreadsheet Model.

The carbon abatement schedule is not static in time. For example, new technology can create new carbon-reducing activities, or reduce the price of existing ones. And scarcity (e.g. of land suitable for forest planting) can increase the price of existing activities, as can competition for resources from other activities.

Private action won’t happen immediately. Nor may it happen at all if the expected profit margin is small (e.g. a $70 cost vs. a $72 ETS price). That said, over time we can expect most profitable activities to be pursued by someone.

An alternative to such subsidies is government intervention to push up the ETS price by, for example, purchasing extant units or cutting back on the supply of new units.

Another very helpful analysis from Dave Heatley. Of course we should adopt the least costly mitigation measures first. This issue has obviously been afflicted with political agendas, where a certain class of people in politics, media, planning and bureaucracy see an opportunity in climate change, to push an agenda they wish to impose anyway. For example, a general distaste for freedom, cars, roads, and decent family housing at an affordable price that allows the Proles too much scope to breed. So in the name of "carbon mitigation" we heavily subsidize public transport, a majority of which (routes, times of day) operate LESS efficiently than an average car with only the driver on board.

Wherever one finds an unwillingness to simply price carbon and let free people and markets pursue 1000 different solutions, one finds a crypto-totalitarian mindset that is just using climate change as a pretext. Or, if they are in good faith and just don't understand the complexities, they are the wrong people to be anywhere near the levers of decision making for society. There is an evident problem already, in that the people intent on forcing higher-density living on the population, refuse to see their responsibility for housing now costing a family three times as much over their lifetime, as it used to in "the bad old days".

There is another big conceptual problem with the whole issue, in that there is no honest confrontation of the cost of mitigating ALL temperature rise, as opposed to hysterical promotion of mitigation measures that the establishment regards as "desirable", using language that sounds as though doing these things will avert the entire climate disaster, rather than delay it a few weeks or some fraction of a fraction of 1 percent, if at all. And furthermore, there is no honest comparison of this cost versus the cost of ADAPTING. There is really 3 costs to include in the analysis: the cost of mitigation, the cost of adaptation, and the cost of impacts against which we fail to mitigate or adapt. So far, despite the hysteria with which rail investment, public transport investment, and urban intensification are promoted, we would not by these means avert more than a tiny fraction of the "costs of climate change", if at all. It is not just that there are a lot of people on the planet who might not follow our noble example, it is that these strategies are little more than tokenism anyway. There is also a downside in that impacts of climate events may well be costlier to populations who have been concentrated IN harm's way instead of out of it. More "urban sprawl" rather than less may well be a cost-reducer in the whole equation. If free people were simply changing their behavior in response to price signals, and technology and entrepreneurship were responding to the price signals, many people may well end up living close to nature at low density, there are numerous "sustainability" mechanisms that are a good fit with this, while "concrete jungle" elite-approved urban form foregoes numerous opportunities that might be LOW cost mitigation.

You write:

"What is more important here is how to interpret and use SC-CO2 in policy decisions. $350 is not a target for what other prices should be. Rather, it is an *upper limit*, that is, the most society should be willing to pay to avoid a tonne of carbon emissions" (my emphasis)

This is incorrect. Only if we had an *infallible* estimate of the SCC would it follow that abatement that costs more than the SCC would be reduce aggregate well-being. But we don't have such an estimate. This is from the Rennert et al. piece you quote:

"A limitation of this study is that other categories of climate damages—including additional non-market damages other than human mortality—remain unaccounted for. The inclusion of additional damage sectors such as biodiversity, labour productivity conflict and migration in future work would further improve our estimates. Current evidence strongly suggests that including these sectors would raise the estimates of the SC-CO2, although accounting for adaptation responses could potentially counteract some of that effect. Other costs of climate change, including the loss of cultural heritage, particular ways of life, or valued ecosystems, may never be fully valued in economic terms but would also probably raise the SC-CO2 beyond the estimates presented here."

In light of these serious limitations, it would be a mistake to treat the $350 as an "upper limit" in the way you suggest in the post.