Land covenants redux

Restrictive land covenants are a tool of the state planning system, not just a neighbour-to-neighbour contract or club

My post Land covenants: Why pay to limit your options? characterised restrictive land covenants in subdivisions as contracts that create clubs of neighbours, with rules designed to manage between-neighbour externalities.

However, my explanation left some loose threads, and investigating these has convinced me that there is a lot more going on. In addition to the functions in my original post, restrictive land covenants:

manage conflicts between the developer and landowners during the period between the first and last land sales in a new subdivision (or group of subdivisions); and

provide local government with rule-making and rule-enforcement mechanisms, potentially beyond those specified in legislation and formal planning documents.

This second function is particularly surprising, as it allows local council decision-makers to bind future councils in ways that are not obvious from the Resource Management Act 1991.1

Loose thread 1: Who gets to write the rules?

In the model described in my post, developers use information, presumably gleaned from the experience of other developers and perhaps lawyers, to design a set of club rules that will, they believe (or hope), maximise the total price they receive from selling sections. Chris Parker drew my attention to a second purpose of land covenants — as a contract between the developer and land purchasers, to manage risks to the developer.

Property developers write the covenants before they sell the first section in their new subdivision. But the developer remains an interested party until they sell the last section in that subdivision, or even the last section in that area in the case of a staged development. Should the initial buyers despoil the look of the subdivision, for example by appearing to move permanently into temporary structures, this may discourage further buyers. Developers also face the risk of post-contractual opportunism by early buyers — they might, for example, become NIMBYs and take action to stymie the completion of the development.

Developers could presumably deal with these issues through contractual agreements with land purchasers, though covenants have the advantage of binding subsequent owners. Overall, this seems a benign use of covenants. But it would make a lot of sense if developer-friendly clauses expired along with the developer’s interests, rather than becoming a permanent fixture.

Loose thread 2: Why do covenants include clauses that benefit the local council?

I’ve been digging deeper in another direction. A few of the clauses in the covenant I used as an example in Land covenants: Why pay to limit your options? didn’t make a lot of sense in the context of a club of neighbours. The apparent beneficiary of these clauses was the local council. For example:

not to plant anything on the “list of Plant Pests” maintained by any “local government authority having governance over the lot”; and

not to call upon the “District Council to pay for or contribute toward the expense of construction or maintenance of any fence”.

So I took a look at the resource consent decision for that subdivision. It was clear that the covenant is the end result of bargaining between the developer and representatives of the district and regional council.

Indeed, that resource consent both requires a land covenant and regulates its contents. Specifically, it states:

“that a restrictive covenant of the general form as provided [in draft form] shall be prepared and registered against the new certificates for title for [all] lots within this subdivision by the consent holder at the consent holder’s cost”.

And further requires some specific modifications to the developer’s draft of the covenant, including adding and removing some conditions.

This makes restrictive covenants an instrument of the planning system, and one that:

allows for council staff (and others) to bargain for restrictions that exceed those in District Plans (while neatly sidestepping the public scrutiny that such Plans attract);

relies on private enforcement rather than council enforcement; and

can bind future councils in a way that a normal resource consent cannot.

This opens a can of worms. I can see some ramifications, but I’m sure there are many others. It is clear, though, that if regulation of residential land covenants is desirable for the reasons outlined in these posts, then local government should not be the regulator.

I’m not a fan of public law systems using private enforcement to create more rigidity, having learnt of the example of Texas abortion laws. Further, I don’t think it is in the public interest that councils can bind the actions of future councils in this way. Future councils might legitimately decide, for example, that granny flats and future subdivisions are socially desirable; the current council should not be signing off on covenants that permanently prohibit them.

By Dave Heatley

Bonus material

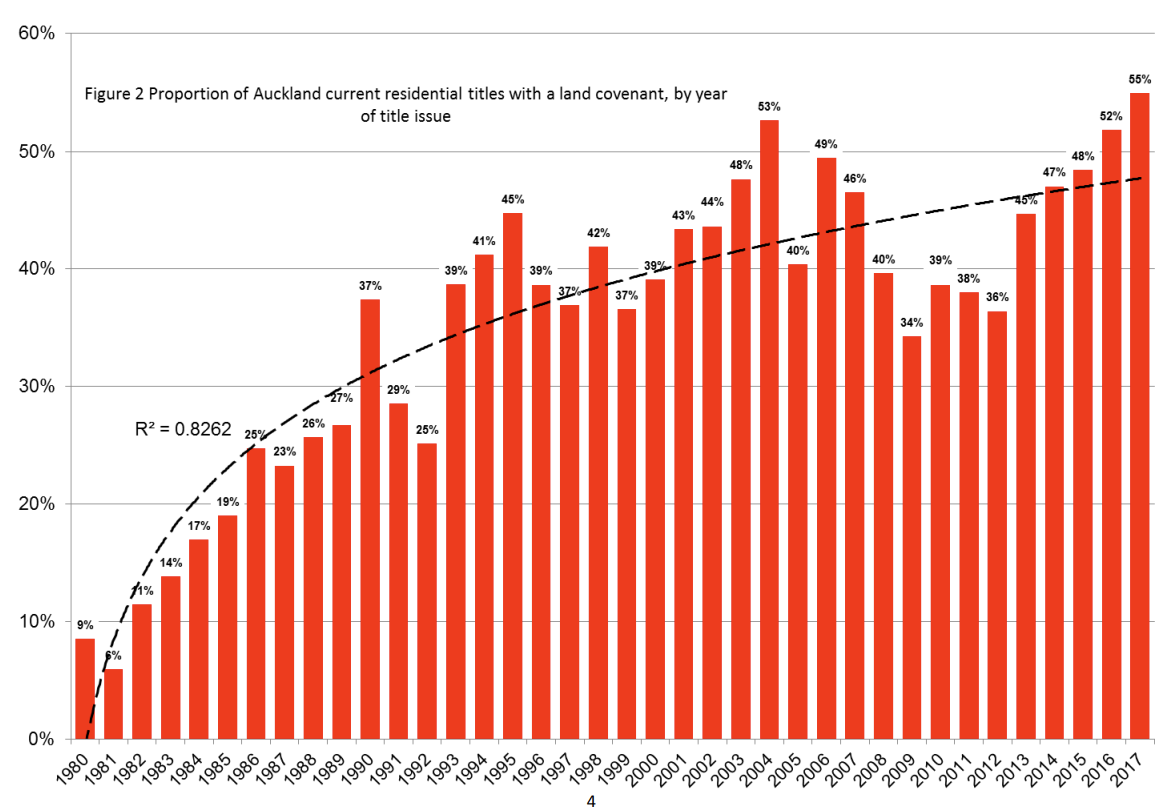

A graph showing the growth in the use of land covenants in Auckland over the past 40 years.

Look here for an online example of a restrictive land covenant. This one requires, among other things, a dwellinghouse/primary building with a minimum floor area of 120 square metres, and a minimum of one garage, which is to be attached to the dwellinghouse/primary building. On the positive side, this covenant has an expiry date of 2035.

”Covenant” appears 27 times in the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA). These appearances seem to relate to covenants created for specific purposes, and solely between the consenting authority (e.g. the District Council) and the consent holder (e.g. the subdivision developer). Nothing I can see gives consenting authorities a specific power to control or require covenants between other land-owners. But nor does the Act prohibit them doing so. I’d be interested to hear the views of legal and planning specialists on this.

The NZ Parliament is currently considering the Natural and Built Environment Bill (NBE), intended as a replacement for the RMA. The references to “covenant” in the NBE appear to reproduce those in the RMA, so I don’t expect any changes to the use of land covenants should the NBE be passed.