2B RED: Law and Orr-der

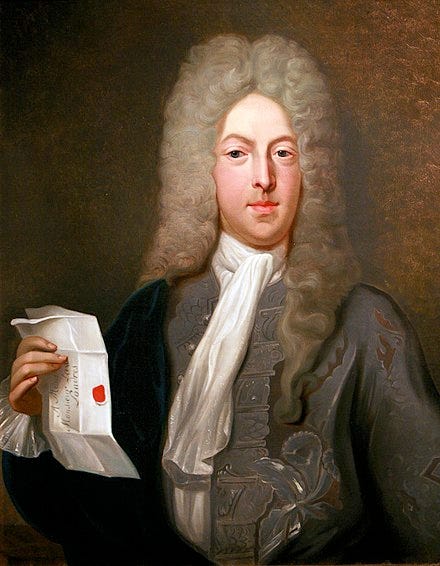

John Law - gambler, murderer, fugitive, philanthropist, adventurer & central banker

Monetary policy ambles along

For an extended period after the 1980s (think Volkerism) monetary policy ambled along (yawn). Of course we had the Global Financial Crisis, but that was created by foolish lending policies rather than monetary policy per se. Inflation had seemingly been brought under control in many countries (we'll excuse Zimbabwe and Venezuela, where in the latter, inflation is down to a mere 650% p.a., a remarkable achievement of monetary policy as it was 130,060% as recently as 2018).

Back home under the long white cloud, for three decades from December 1991 until March 2021, inflation rates were typically low, admittedly with a few odd upward blips. In fact, the annual inflation rate as measured by the CPI averaged 2.0% over this entire period. And if we recognise that the measured inflation rate is subject to an upward bias, the "true" rate of inflation might well have averaged little more than 1% p.a. So we can safely predict that the average punter in the pub in Lumsden was not paying a whole lot of attention to the finer points of monetary policy; in fact to misquote the non-esteemed Sir Robert Muldoon: "the typical person in the street wouldn't recognise monetary policy if they fell over it".

Until it doesn’t

But along came Covid, and suddenly central banks hit the front pages. New vocabulary sprung up and we were peppered with new acronyms: Stress Testing (ST)1, Quantitative Easing (QE), Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAP), Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), Zero Lower Bound (ZLB) and yes, Negative Interest Rates (NIR). Central banks, including New Zealand’s, were catapulted out of their comfort zones as they grappled with the role of the monetary and financial systems to address economic stabilisation and recovery, while maintaining appropriate prudential strategies and providing (at least some) transparency.

With all this heightened interest in monetary policy, 2B RED thought it would be timely to look at a little history. Specifically, James Buchan’s John Law: A Scottish Adventurer of the Eighteenth Century.2 Law was a remarkable Scot who is arguably a key person in the history of modern monetary systems. His story has some salutary lessons, which remain relevant today.

Who was John Law?

He was a gambler, a murderer, a fugitive, a banker, a philanthropist, and an adventurer. Alfred Marshall described him as reckless and unbalanced,but a most fascinating genius. Law’s CV includes what in today's parlance would be the French Minister of Finance and Governor of the Central Bank. But let's not get ahead of a good yarn.

He was born in Edinburgh in 1671. His father was a goldsmith, and at age 14 the wee laddie was apprenticed to his Dad's business. As goldsmiths were early bankers who accepted deposits and made loans, and whose certificates were traded and used in transactions between third parties, John learned some basics about banking.

As a young man he moved to London and in the course of fighting a duel with swords, killed his opponent, and was convicted of murder. However he escapes from prison and flees to France, being "on the lam" (i.e. a fugitive from Englishlaw). But he was not about to disappear quietly into the bucolic peace of a remote French village, and spend his days gardening and making wine. Oh, no. That was not the style of John Law. He is moving around Europe: Venice, Paris, Amsterdam drinking, womanising and above all gambling. By starting a gambling table, he sets himself up as the banker, on the grounds the house is always a net winner. He had a sound grasp of mathematics and probability, and as an expert in statistics was renowned for mentally calculating the odds. The result is he becomes extremely wealthy.

Supplying the Nation with Money

But he is also pursuing another agenda. He returned to Scotland and wrote a treatise entitled Money and Trade Consider'd with a Proposal for Supplying the Nation with Money.

Law called for the creation of a national (central) bank which would issue paper money backed by silver or gold. But he couldn't convince the leading burghers of his scheme; and with the 1707 Union joining Scotland and England he now had to flee from his homeland — and back to France.

He ingratiated himself with the Regent, the Duke of Orleans, who was ruling France in lieu of King Louis XV, who had inherited the throne at the age of 5. This led to his being granted royal approval to apply his proposal for a monetary system, which incidentally appealed to the Regent due to the promise to reduce the public debt. Law created the Banque Generale based on what today we know as fractional banking, in which the paper was only partially backed by silver. It was in effect France's central bank, with Law as governor. The Regent, duly impressed with Law's scheme, in 1720 appointed him as Controller General of the King's Finances, or effectively Treasurer and Minister of Finance.

Law managed these matters of the kingdom in a way that generated a significant personal return, adding to his wealth. He was generous however, and gave considerable sums for the restoration of churches throughout France. He also sought to rationalise fiscal policy by buying out with his own funds, petty funcionaries who had rights to collect a myriad of minor taxes on soap, fish, salt and firewood, or held positions aswine inspectors, beer tasters and cart certifiers (and early form of a warrant of fitness).

French society continued to heap honours on Law. He was elected as an Honorary Fellow of the Acadamie Royale des Sciences, an exclusive club reserved for French citizens who were experts in mathematics or physics.

Scope creep — and a bank run

His success however led to scope creep. He floated a private enterprise known as the Mississippi Company, whose aim was to support the establishment and development of the French colony of Louisiana. Government debt was converted into shares in the company, much to the Regent's pleasure.3 The company constantly expanded its activities covering, ship building, fishing fleets, Paris real estate, and had monopoly control of the beaver fur trade and the slave trade. It was renamed the Compagnie Perpétuelle des Indes, and was absorbed into the bank. At its height, the whole integrated operation had a capitalisation equivalent to twice the GDP of France.

But eventually, the inevitable happened and speculators lost faith in the company shares, leading to a run on the bank and a calamitous fall in the share price. The whole apparatus collapsed and Law eventually died bankrupt in Venice in 1729.

Undoubtedly we should give him credit for his vision of a fractional banking system.

Lessons for central banking

There are lessons for central banking from the story of John Law.

Maintaining confidence and credibility is paramount

Maintaining control of the money supply, avoiding excessive and rapid money creation

Maintaining independence from direct involvement by the rulers

Above all stay focussed on the primary function of a central bank and avoid involvement in extraneous matters and ventures.

"Humility rather than hubris should have conditioned monetary policy right from the start" (William White),4 is equally applicable to Law as to today's central bankers.

2B RED is reliably informed that “stress testing” does not refer to taking the blood pressure of the Governor.

James Buchan (2018) John Law: A Scottish Adventurer of the Eighteenth Century (London: Maclehose Press).

A parallel development in England saw Sir John Blunt establish the South Sea Company, a public-private partnership in which government debt was converted into shares in the company.

From the Foreword in Graeme Wheeler & Bryce Wilkinson (2022) How Central Bank Mistakes after 2019 led to Inflation (Wellington: New Zealand Initiative).

Progressing into the present we bump into the concept of 'decolonisation'. I found the book by Kojo Koram 'Uncommon Wealth Britain and the Aftermath of the Empire' very interesting reading.