The history of the theory of production in one figure

Everything you wanted to know ... but were afraid (or bored) to ask

This post is based on “(Almost) everything you wanted to know about the history of the theory of production/the firm: but were afraid (too bored) to ask”, forthcoming in New Zealand Economics Papers. Thanks to Philip Meguire for his assistance with this post.

A picture, worth a thousand words

William Letwin writes that “[b]efore 1660 economics did not exist; by 1776 it existed in profusion” (Letwin 1964: vii) and this is largely true for the particular case of the theory of production. Through time we have seen various approaches being taken to the analysis of production and the firm within the mainstream of economic investigation. These approaches have run the gamut from normative analysis to positive analysis, from macroeconomics to microeconomics to micro-microeconomics and from theories of production to theories of the firm. The figure below outlines developments.

That 70s show

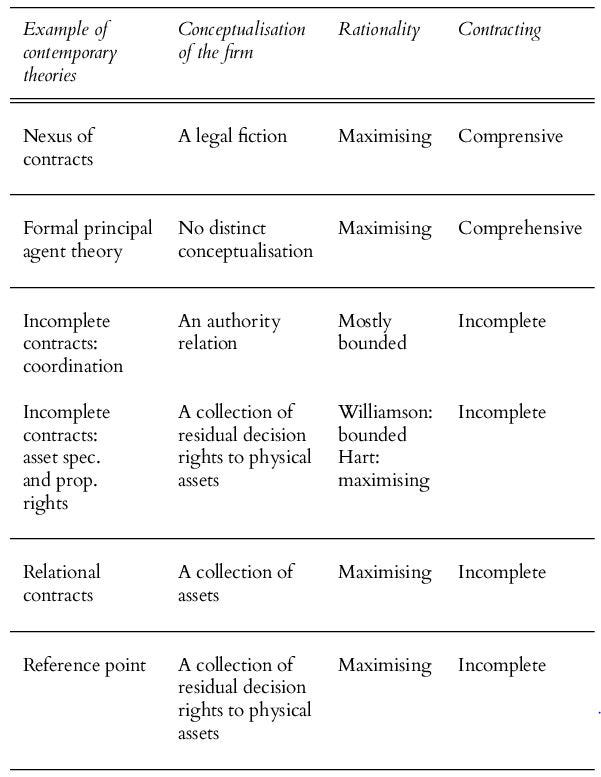

From the figure, we see that chronologically theories of production preceded theories of the firm. While not entirely accurate, 1970 is nonetheless a convenient dividing line between the theory of production and the theory of the firm proper. It was around this time that the theory of production began to be supplemented by a genuine theory of the firm. A distinguishing feature of much of the post-1970 literature is that it takes an incomplete contracts and maximising approach to modelling the firm. But not all contemporary approaches employ this particular combination of contracting and rationality however, some use comprehensive contracts theory while others utilise bounded rationality and incomplete contracts, see the table below.1

Before the 1970s the standard mainstream analysis of production/the firm was implicitly a complete contracts approach. This limited the applicability of their theories to the firm. As Oliver Hart (2003, p. C70) has emphasised, the complete contract theories can say little about the important questions to do with the firm,

"[...] if the only imperfections are those arising from moral hazard or asymmetric information, organisational form – including ownership and firm boundaries – does not matter: an owner has no special power or rights since everything is specified in an initial contract (at least among the things that can ever be specified). In contrast, ownership does matter when contracts are incomplete: the owner of an asset or firm can then make all decisions concerning the asset or firm that are not included in an initial contract (the owner has ‘residual control rights’)."

Small is beautiful

From, roughly, the 1930s to the 1970s what often went under the heading of the theory of the firm was, in reality, a theory of micro-level production. But, significantly, it was production without firms. Firms are unnecessary in a world of zero transaction costs (Coase, 1937). The organising framework was that of market structure, eg. monopoly, oligopoly, perfect competition, etc.

Before the 1930s the microeconomic approaches to production also concentrated on market structure rather than the firm itself. The proto-neoclassicals created theories of monopoly, oligopoly and an only partially developed theory of perfect competition. The leading attempt at modelling production in the post-1870s neoclassical period was Marshall’s ‘representative firm’.

Thinking big

Before these micro approaches came the modelling of aggregate or macroeconomic production. This began in the sixteenth century with the mercantilists, and continued with the physiocrats and the classical economists.

Ethics, not economics

For the period before the 1500s the predominant approach to production was ethically or religious based. The questions asked were mainly normative with little attempt made to consider production from a positive perspective. Questions were asked about what should be produced or what production or occupations would find favour with God or what production was ethically justified. As Whittaker (1940, p. 362) explains, with respect to the early Christian era, “[i]n production, as in everything else, the Christian man was to be a servant of God, occupying himself only in those activities that received divine favor”.

Moving from a normative to a positive framework set a chain of developments in motion which, eventually, resulted in the contemporary theories of production and the firm. We will briefly outline this sequence of events up to 1970 beginning with aggregate approaches to production.

The State replaces God

Whittaker (1940, p. 716) argues that in medieval Europe economic thought was subordinate to Christian morals, and it was only with the appearance of mercantilism that this changed. He suggests that within mercantilism the State replaced God in the discussion of wealth and production. Mercantilism requires a dominant state to create and enforce monopolies, as well as to regulate and control both domestic and international trade and direct the economy in general. While there is discussion of production/the firm in the mercantilist literature, it is a limited discussion — limited both in the sense that it deals not with issues to do with firms per se, but rather with the effects of firms on more macro issues such as the balance of trade, and in the sense that it deals mostly with the regulated companies and their monopolies.

While the regulated companies often came under attack, for various reasons, they were not without their defenders. But it is important to note that many of the arguments made were simply partisan rent-seeking, with each side just dressing up their position in terms of the general welfare. It is also worth observing that the arguments made were more policy-relevant than theory relevant. Although the debates involve ‘firms’, they did not require a theory of the firm or firm-level production. For the evaluation of policy, there is no need for any explanation of what a firm is, what its boundaries are or what its internal organisation is. As limited as the discussion was, it was, importantly, a positive analysis.

The French connection

In chronological order, the mercantilists were followed by the physiocrats. Physiocracy aimed to analyse the determinants of the general level of economic activity and such an endeavour required a positive framework. Within physiocracy, the key factor determining the level of economic activity was the capacity of agriculture to yield a ‘net product’. By this, the physiocrats meant that the wealth of a nation was determined by the size of any surplus of agricultural production over and above whatever is required to support agriculture (by feeding farm labourers etc). It was argued that it was only when labour was applied to land that it created a surplus which was over and above what was required for its maintenance. It was out of this surplus that all other classes in society were supported. Agriculture alone was productive, it alone produced the ‘net product’. Other classes in society were stipendiary, sterile or unproductive.

To see the difference between productive and unproductive note that the physiocrats believed that the artisan sold his output for a payment that covered (1) his production costs plus (2) subsistence wages for himself; while the cultivator received an amount that covered (1) his production costs plus (2) his subsistence wages plus (3) a surplus, which would be paid to the landowner as a rent. Thus productive means productive of a surplus (Whittaker, 1940, pp. 369–70).

Giorgio Gilibert argues that the physician and leading physiocrat Francois Quesnay saw agriculture as productive because, as noted above, it generated a surplus (rent). But non-agricultural activities could be seen as productive if the assumption that rent was the only form of surplus was dropped. If profit is seen as a legitimate form of surplus then other activities can be productive. Adam Smith and the classical economists made this move (Gilibert, 2008, p. 823).

Production takes centre stage

With the development of classical economics, production became one of the main topics of political economy. Cannon (1917, p. 28) comments that

“[b]efore the middle of the eighteenth century a theory of production can scarcely be said to have existed.”

He adds when surveying early English economic treatises that,

“ ‘Production’ and ‘Distribution’ do not seem, however, to have been used in England before 1821 as titles of divisions of political economy; and, before Adam Smith wrote, they were not in any sense technical economic terms” (p. 26).

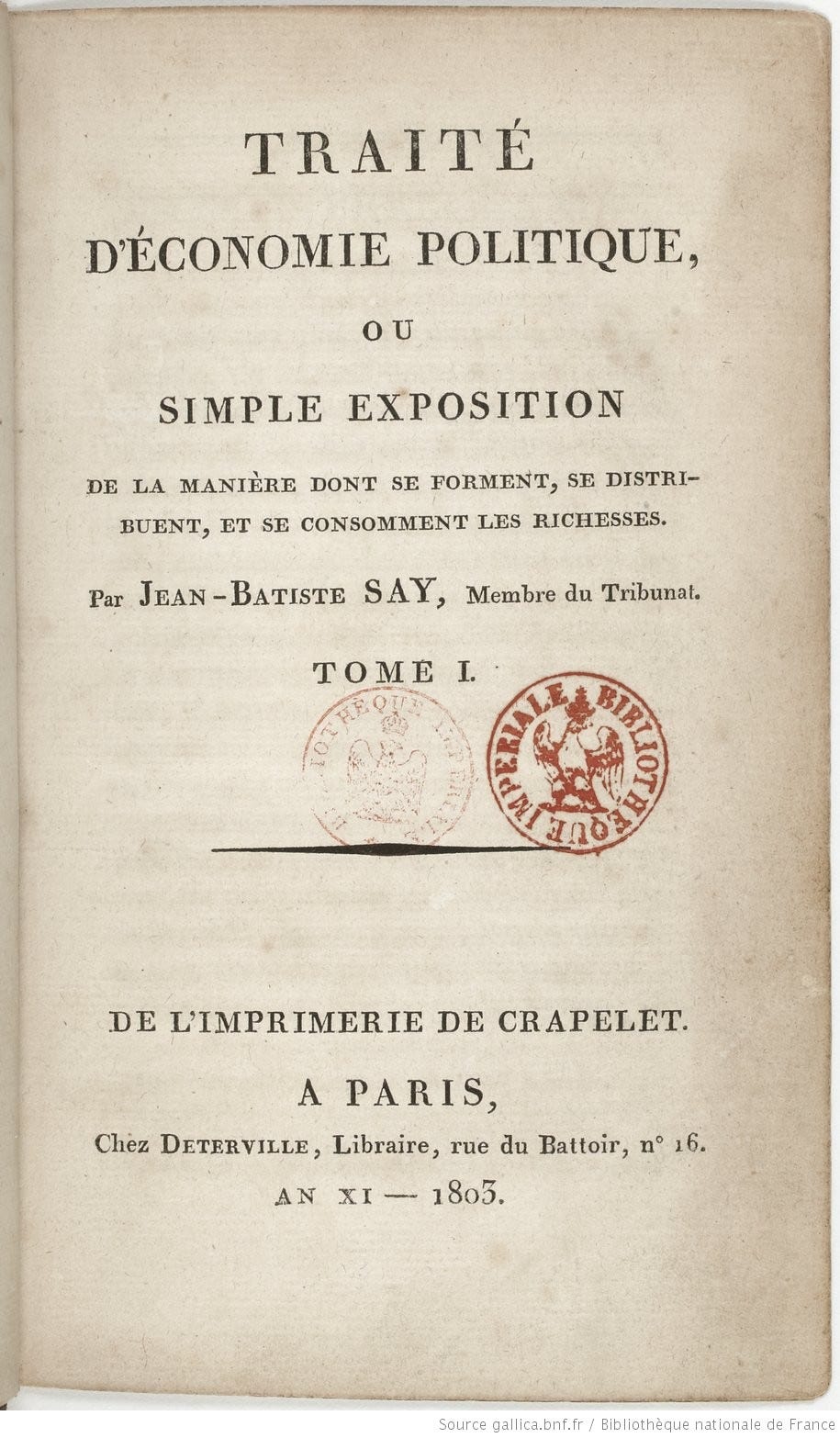

Post-Smith, production became one of the major divisions of economics. One example of this new emphasis can be seen in Book 1 of the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Say’s 1803 book, Traité d'économie politique ou simple exposition de la manière dont se forment, se distribuent et se composent les richesses (Treatise on Political Economy, or A Simple Exposition of the Manner in Which Wealth is Formed, Distributed and Composed) which is entitled ‘On Production’.2 Some forty-seven chapters are devoted to the discussion with the factors of production being land, labour and capital.3 In 1821 Scots-born James Mill, following Say, opened his Elements of Political Economy with a chapter on ‘Production’, which he divided into two sections: labour and capital. Another example is chapter two of Irish-born Robert Torrens’s An Essay on the Production of Wealth, also published in 1821, which is devoted to production with his ‘instruments of production’ being land, labour and capital.

The classical economists followed the mercantilists and physiocrats in that their general approach to the economy was predominately macroeconomic. O’Brien (2003, p. 112) remarks that,

“[c]lassical economics ruled economic thought for about 100 years [roughly 1770-1870]. It focused on macroeconomic issues and economic growth. Because the growth was taking place in an open economy, with a currency that (except during 1797-1819) was convertible into gold, the classical writers were necessarily concerned with the balance of payments, the money supply, and the price level. Monetary theory occupied a central place, and their achievements in this area were substantial and — with their trade theory — are still with us today”.

Thus the theory of production that emerged from classical economics aimed to explain the production of an entire economy. Edwin Cannan writes, concerning the period 1776-1848,

“ ‘Production’ and ‘distribution’ in political economy have always meant the production and distribution of wealth” (Cannan,1917, p. 1).

This is the opening sentence of a chapter on “The Wealth of a Nation” (Cannan, 1917, chapter 1). It was the production of aggregate wealth that was an issue of interest.

But, importantly, their theory was a positive theory of aggregate production that did not have the ethical overtones of the pre-seventeenth century writers. This set the tone for the theories, including the microeconomic theories, that followed.

The French connection 2

Antoine Augustin Cournot’s major economics work was Researches into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth (Cournot, 1838). It is this work that first laid out our basic models of monopoly, duopoly, oligopoly and the beginnings of perfect competition. That is, this work supplied us with our basic microeconomics models of market structure.

While Cournot is known to all economists today, it required something of a rediscovery in the 1960s for him to become a standard part of the economic landscape. It was only after the usefulness of game theory become recognised, and it was realised that the Cournot equilibrium is just a form of the Nash equilibrium, that Cournot become hailed as an economic innovator.

But Cournot’s famous contributions can be seen more as theories of industries or markets, rather than as theories of the firm per se. In modern terms, he was doing industrial organisation rather than organisational economics.4

Cournot has been described as a ‘proto-neoclassical’. Proto-neoclassicals are pre-1870 writers who were developing neoclassical-like techniques before the commonly accepted founding of neoclassical economics by Jevons, Menger and Walras in the 1870s. After its inception, the most important contribution to neoclassical economics was made by Alfred Marshall who codified these, at the time, new ideas for economists with the publication of his hugely influential book Principles of Economics in 1890.

Marshalling the troops firms

In his Principles, Marshall’s approach to production makes use of the idea of the ‘representative firm’. Hartley (1996) starts his exploration of the representative firm by arguing that Marshall’s motivation for creating the representative firm was to avoid having to assume that all firms were identical.

The representative firm was part of Marshall’s answer to the problem of constructing an industry supply curve, which shows in a two-dimensional (own-price/output) space an inclusive relationship involving other prices and other quantities. In such an environment a movement along the supply curve involves a change in many economic variables, such as input prices and other product prices.

Note that for Marshall a supply schedule shows what the minimum price has to be to ensure producers are willing to produce a particular quantity. This minimum price must cover the average costs of the highest-cost producer and the supply curve shows how these costs change as the industry output increases. This stands in sharp contrast to the now-standard microeconomic textbook approach to industry supply in which all prices are assumed to be constant apart from the price of a particular commodity, and then output – of both the individual price-taking firm and of the industry — is taken to be a function of only that price (Opocher & Steedman, 2008, p. 247). The modern supply curve shows how much an industry will supply at any given price.

Marshall gave us the famous metaphor of an industry being like a forest — while it might appear unchanged if considered as a whole, the individual trees that make it up are constantly changing. It was to reconcile his dynamic view of individual firms with the static view of industries that Marshall introduced the idea of the representative firm. The representative firm incorporates the relevant cost and business conditions of all firms in the industry.

Controversy ensued

What is now referred to as the ‘cost controversy’ consisted of a series of papers published in the 1920s and early 1930s which debated aspects of Marshallian economics. The representative firm was a casualty of this controversy. Wolfe (1954) places responsibility for the expunging of the representative firm from the economics literature firmly at the feet of two papers, Sraffa (1926) and Robbins (1928).

Hartley (1996, pp. 172–174) summarises the attacks on the representative firm by arguing that they made four major claims:

(1) Robbins claimed the representative firm was ephemeral.

(2) He also argued that its use gained nothing.

“There is no more need for us to assume a representative firm or representative producer, than there is for us to assume a representative piece of land, a representative machine, or a representative worker” (Robbins, 1928, p. 393, emphases in original, footnote deleted).

Marshall used the representative firm to show how heterogeneous firms could generate a single market price but Sraffa (1926) argued that in equilibrium different producers could charge different prices for similar commodities. In modern terms think of, for example, monopolistic competition. Thus there is no need for the representative firm.

(3) Young (1928) showed that the representative firm can not account for economic expansion other than that generated by the expansion of current manufacturing processes. Marshall’s view was that as an industry grew the representative firm grew proportionally. This is what is meant by the supply curve remaining relevant. Young (1928) pointed out that as the economy grew the division of labour expanded so that commodities once produced by one firm could now be made by multiple firms, each single firm specialising in producing just one part of the good. Young (1928, p. 538) writes

“[w]ith the extension of the division of labour among industries the representative firm, like the industry of which it is a part, loses its identity. Its internal economies dissolve into the internal and external economies of the more highly specialised undertakings which are its successors, and are supplemented by new economies”.

Thus if we have growth we must ask, what happens to the representative firm? During a period of growth, the representative firm may cease to be representative. Even if all firms are the same, and growth occurs due to an increase in the number of firms, then the representative firm does not grow with the industry.

(4) Robbins (1928, p. 399) writes

“The whole conception, it may be suggested, is open to the general criticism that it cloaks the essential heterogeneity of productive factors–in particular the heterogeneity of managerial ability–just at that point at which it is most desirable to exhibit it most vividly”.

The reason Marshall created the representative firm in the first place was to create a single supply curve with heterogeneous firms. Implicit in this formulation is the idea that the supply curve will be the supply curve of the representative firm. But why? Why not some other firm? The marginal firm, for example. Marshall argues that if a manager sees the representative firm making profits he will enter the market. This increases supply and forces down the market price. This process will end when the price equals the costs of the representative firm and hence this firm’s profits will be zero. But for price to equal the costs of the representative firm, all managers would have to be of average ability. If there were managers of superior or inferior ability the supply price could be forced away from the representative firm’s cost to some other firm’s costs, e.g. the marginal firm’s costs. But by assuming that managers are all average Marshall is forgetting the heterogeneities he began with.

These criticisms were remarkably effective the representative firm was driven from the literature remarkably quickly.

Equilibrium (firm) is reached

In response to the attacks, A. C. Pigou argued (Pigou 1928) that for carrying out comparative static analysis,

“Marshall’s highly complex analytical starting point in a population of heterogenous disequilibrium firms was, strictly speaking, unnecessary. Pigou insisted on the possibility-and, indeed, desirability-of eliminating this complexity” (Foss, 1994, p. 1121).

Pigou’s elimination of complexity involved the introduction of the now standard ‘equilibrium firm’.

So the representative firm was replaced with little difficulty in part because there was a ready-made replacement. Today the textbook model of the ‘firm’ (or more correctly the neoclassical model of micro-production) is based not on Marshall, but rather on Pigou. The equilibrium firm has become the standard.

Including Pigou’s creation of the equilibrium firm (Pigou 1928), Moss (1984) argues that there were three steps in the development of the neoclassical theory of production:

“[w]ithout Pigou’s analytical use of the industry [step one] and his invention of the equilibrium firm [step two], we could not have had the ‘firm’ of the neoclassical theory. None the less, the now conventional conception of the firm was left incomplete by Pigou in two respects. First, Pigou himself did not assume that the industry was comprised entirely of equilibrium firms, but only that an equilibrium firm could be constructed from the law of returns (increasing, constant or diminishing) obeyed by any industry. Second, Pigou did not assume the firm qua production function to be facing household preference functions. It was the inclusion of these two elements that constituted the third step in the creation of the firm analysed in the neoclassical theory of the firm”.

Although there were some preliminaries “[…] this final step was completed by Robinson (1933) and Chamberlin (1933)” (Moss, 1984, p. 313).

Note this third step was the kind of assumption Marshall tried so hard not to make. Robinson and Chamberlin made the move in their models of imperfect competition and monopolistic competition, respectively (Chamberlin, 1933; Robinson, 1933). In these models, industries are comprised entirely of equilibrium firms which have identical cost curves, and firms, as production functions, faced household preference (demand) functions. But as Moss (1984, p. 314) also points out,

“[b]y assuming that every firm in the industry has an identical cost curve, Robinson and Chamberlin stood Pigou’s construction of the equilibrium firm on its head. Where Pigou argued that an equilibrium firm could be derived from the laws of returns obeyed by any particular industry, Robinson and Chamberlin defined the industry on the basis of a population of equilibrium firms”.

With this change in the interpretation of the relationship between the equilibrium firm and the industry, the neoclassical approach to production had finally developed.

Thinking big good, thinking small better

The first of the positive mainstream theories of production were theories of aggregate production which aimed to explain the production of the economy as a whole. These theories were driven by the issues that the mercantilists and physiocrats were addressing. Issues to do with the wealth of a country, the balance of trade or the drivers of economic activity require a positive theory of wealth and production but it is a theory of aggregate wealth and production. The classical economists were also primarily concerned with macroeconomic problems such as growth, trade, the balance of payments, the money supply and the price level and their modelling of production reflected this.

The beginning of mainstream micro-level production theory is Cournot’s theories of monopoly, oligopoly and his initiation of the theory of perfect competition. As O’Brien (2004, p. 67) has emphasised the core of neoclassical economics is the theory of microeconomic allocation. This emphasis meant that relative prices become the principal object of analysis. This analysis utilised micro-level theories rather than the macro-level theories of previous generations of economists.

No firms please, we’re British (and French)

When considering the representative firm a point worth noting is that Marshall spent much time studying real industries and firms. While these studies certainly influenced his approach to the theory of the firm, there is a tension between his desire to base his representative firm on real firms, and the use of an implicitly zero transaction cost framework for his theoretical modelling of the firm. The use of a zero transaction cost framework implies that there is no role for firms in his theory of production (Coase, 1937).

Zero transaction costs also imply there is perfect and costless contracting. This reinforces the production without firms conclusion since in such a situation “[...] it is hard to see room for anything resembling firms (even one-person firms), since consumers could contract directly with owners of factor services and wouldn’t need the services of the intermediaries known as firms” (Foss, 2000, p. xxiv).

Marshall’s representative firm is therefore not a theory of the firm. The 'firms' that lie along the particular expenses curve5 are just groupings of factors of production bought together and controlled by market contracts. In addition, Marshall’s theory can not answer the three core questions that underlie the post-1970 mainstream theory of the firm:

(1) why do firms exist?

(2) what determines the boundaries of the firm? and

(3) what determines the internal structure of the firm?

Marshall's 'firms' are just collections of cost curves — they have no real existence, no boundaries and no internal organisation. Thus the Marshallian modelling process can be interpreted as one which begins with production involving real firms but ends with a model of production involving no firms at all.

Cournot’s theories of market structure as well as Pigou's equilibrium firm, and therefore the standard neoclassical models of production, are also zero transaction cost models and thus also models of production without firms. These models can not answer the three basic post-1970 questions either. The (proto-)neoclassicals were not interested in the firm as such, they were, to abuse Marshall's famous analogy, more interested in the forest than in the trees.

When smaller is more

In general, as the questions asked began to concern, in a sense, ‘smaller’ units of analysis more micro approaches to production/the firm started to be developed. Harvey Leibenstein has argued that such a move to smaller units of analysis has occurred in most sciences,

“[i]n the life history of most sciences there are movements toward the study of larger aggregates or toward the detailed study of smaller and more fundamental units. My impression is that in most fields the movement toward the study of more micro units has predominated” (Leibenstein, 1979, p. 477).

Macroeconomic problems required a theory of aggregate production, market structure analysis needed a microeconomic theory of production, and when questions finally started to be asked about the existence, boundaries and internal structure of organisations a theory of the firm, involving Leibenstein’s ‘micro-microeconomics’, began to appear. In the 1970s the theory of production was belatedly supplemented by a theory of the firm. It was only then that theories that aimed to answer the three core questions to do with the firm referred to above, came to the fore. It was then that organisational economics began to emerge as a separate discipline. A discipline for which there is no justification for being either afraid of it or bored with it.

By Paul Walker

Originally posted on Anti-Dismal, 11 December 2022.

References

Chamberlin, E. H. (1933). The theory of monopolistic competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cannan, Edwin (1917). A History of the Theories of Production and Distribution in English Political Economy From 1776 to 1848, 3rd edn., London: P. S. King & Son.

Cannan, Edwin (1929). A Review of Economic Theory, London: P. S. King & Son.

Coase, R. H. (1937). ‘The nature of the firm’. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

Foss, N. J. (1994). ‘The biological analogy and the theory of the firm: Marshall and monopolistic competition’. Journal of Economic Issues, 28(4), 1115–1136.

Foss, N. J. (2000). ‘The theory of the firm: An introduction to themes and contributions’. In N. Foss (Ed.), The theory of the firm: Critical perspectives on business and management (pp. xv–lxi). London: Routledge.

Gilibert, G. (2008). ‘Classical theories of production’. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (eds.), The new palgrave: A dictionary of economics, 2nd ed. (pp. 823–826). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hart, O. D. (2003). ‘Incomplete contracts and public ownership: Remarks, and an application to public-private partnerships’. Economic Journal, 113(486), C69–C76. No. 486 Conference Papers March: C69-C76.

Hartley, J. E. (1996). ‘The origins of the representative agent’. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(2), 169–177.

Leibenstein, H. (1979). ‘A branch of economics is missing: Micro-micro theory’. Journal of Economic Literature, 17(2), 477–502.

Letwin, William (1964). The Origins of Scientific Economics. New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

Moss, S. (1984). ‘The history of the theory of the firm from Marshall to Robinson and Chamberlin: The source of positivism in economics’. Economica, 51(203), 307–318.

O’Brien, Denis P. (2003). ‘Classical Economics’. In Warren J. Samuels, Jeff E. Biddle and John B. Davis (eds.), A Companion to the History of Economic Thought (pp. 112-129), Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

O’Brien, Denis P. (2004). The classical economists revisited. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Opocher, A., & Steedman, I. (2008). ‘The industry supply curve: Two different traditions’. The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 15(2), 247–274.

Pigou, A. C. (1928). ‘An analysis of supply’. Economic Journal, 38(150), 238–257.

Robbins, L. (1928). ‘The representative firm’. Economic Journal, 38(151), 387–404.

Robinson, J. (1933). The economics of imperfect competition. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd.

Schenk, H. (2005). ‘Organisational Economics in an Age of Restructuring, or: How to Corporate Strategies Can Harm Your Economy?’ In P. de Gijsel and H. Schenk (eds.), Multidisciplinary Economics: The Birth of a New Economics Faculty in the Netherlands (pp. 333-65), Dordrecht: Springer.

Sraffa, P. (1926). ‘The laws of returns under competitive conditions’. Economic Journal, 36(144), 535–550.

Whittaker, E. (1940). A history of economic ideas. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Wolfe, J. N. (1954). ‘The representative firm’. Economic Journal, 64(254), 337–349.

Young, A. A. (1928). ‘Increasing returns and economic progress’. Economic Journal, 38(152), 527–542.

The most common examples of complete contracts are those implicitly utilised in the textbook partial and general equilibrium models. All states of the world are included and all actions in each state are specified. Comprehensive contracts are those written under asymmetric information such as those found in moral hazard and adverse selection models. In such models, agents can write contracts that have all relevant decisions depending on verifiable variables. To see the difference between complete and comprehensive contracts note that although the optimal contract in a standard principal-agent model will not be first-best — that is, complete — (since it cannot be conditioned directly on variables like effort that are observed by only one party), it will be comprehensive in the sense that it will specify all parties obligations in all future states of the world, to the fullest extent possible. Incomplete contracts are those with missing or unclear provisions. This can be due to the fact that economic actors are only boundedly rational and cannot anticipate all possible contingencies. It might well be that certain states of nature or actions cannot be verified by third parties after they arise, like certain qualities of a good to be traded in the future, and thus cannot be written into an enforceable contract.

Edwin Cannon writes, “Jean-Baptiste Say in his Traité, 1803, seems to be largely responsible for the elevation of Production into a great department worthy of a “Book” or other principal division in treatises on general economic theory” (Cannon, 1929, p. 54).

The organisation of the book changed markedly between the first and second editions.

Organisational economics (OE) is being increasingly differentiated from industrial organisation (IO). Although it must be noted that IO and OE are still closely related areas. IO focuses on output markets while OE focuses more on the firm and input markets. As Schenk (2005: 334) has written, “Thus OE has come to focus on the problems of firms as firms, and not on the problems of the structures within which firms operate and that they themselves — through sometimes quite uncoordinated collective behaviour — create. It could be argued, though, that this is merely a matter of the division of labour among economics subdisciplines. More in particular, it would be the task of the related subdiscipline of Industrial Economics or Industrial Organisation (IO) to focus on organisational issues that are external to individual organisations. Indeed, IO has typically focused on the organisation of markets and its effects upon pricing”.

The particular expenses curve (PEC) is a cumulative array of the average costs of different ‘firms’. The PEC shows the average total costs of the firms involved in the production of the output for a given market price-output combination with the firms arranged in order of efficiency from left to right, with the most efficient firm on the left and the marginal (least efficient) firm at the right.

Thanks this was a very interesting read