Mary Hedges, an NZAE life member and Asymmetric Information groupie, proposes that we revive an AI tradition — the spoof economics paper. AI edition 2 investigated the relationship between NZ’s real GDP growth rate and sheep numbers, discovering the (temporarily famous, but now sadly overlooked) inverted-ewe pattern.1

To further that grand tradition, I’d like to announce the first AI competition — for the best spoof economics paper. Please send an abstract (or even just the outline of an idea) to nzae@substack.com. I am happy to assist with developing it into a potentially award-winning paper.

Entry is open to all AI subscribers. Entries suitable for publication will appear in AI2, and those posted by mid-June 2023 will be eligible for the inaugural AI spoof prize.

No kind deed should go unpunished, so I’ve offered Mary the position of judge. She has graciously accepted. The winning entry will be announced at the next NZAE conference, in June/July 2023.

What counts as a spoof?

We’ll take a wide view as to what qualifies. It should be, or at least pretend to be, grounded in the economics discipline. It could be a ridiculous take on a serious matter, or a straight take on a out-there subject. It may well meet the Ig Nobel prize-winning criterion — to “make you laugh, then think”. Then again, perhaps a good spoof is one that you read to the end, desperately unsure whether or not you are being spoofed.3

To kick-start the competition, I offer the following paper.4

The economics of kindness

By Dave Heatley

Ideas are getting harder to find (Bloom et al. 2020). Yet the numbers of academic papers published each year have surged to more than 7 million (Fire & Guestrin 2019). With this intense competitive activity, it’s hard to imagine a sod left unturned, let alone a field left unexplored. But history tells us that occasionally a new field does emerge, and somebody, somewhere gets to be the first to write it up.

Academic economist responses to the recently identified field “economics of kindness” (Ardern 2019) have been muted to the point of non-existence. Google Scholar, searched on 26 September 2022, reported only 22 matches to the search string “economics of kindness”, and just 7 for “kindness economics”. None provided a useful definition from an economic perspective.

Ardern linked the attribute of kindness to wellbeing economics (Bentham 1790; Easterlin 1974) but she provided neither a definition nor an analysis of the economics of kindness. So, in this paper I take up an infrequent opportunity — to map out a new field of economics.

What’s economics got to do with kindness?

kindness noun: the quality of being friendly, generous, and considerate / a kind act (Oxford English Dictionary 2022)

Kindness is one of the seven capital virtues, along with chastity, temperance, charity, diligence, patience and humility (Wikipedia contributors 2022). (These stand in opposition to the more familiar seven deadly sins.) Note that kindness is a separate virtue from charity, the latter being well-studied (as altruism) in the economics literature.

Virtues are not costless — if they were, then presumably they would be in plentiful supply! They fall within the purview of economics, because

economics is about the choices we make when we cannot have everything we want and the implications of those choices in market and nonmarket settings. As long as people do not have infinite amounts of time and money, economics will have something to say about how they behave in settings involving love and compassion, duty and honor. The essence of economics is remembering that few virtues are absolute—when they get more expensive, harder to do, or less pleasant, people will do less of them. (Roberts n.d.)

What type of economic good is kindness?

Practice random acts of kindness (Herbert 1982)

Acts of kindness have a producer and a consumer. This fits with the economic concept of a transaction.

Each person has at his disposal a certain amount of love, of admiration, and of power, as well as of labor or money or energy, and these must all be distributed. It is reasonable to suppose that they are distributed with the intention of maximizing one’s own satisfactions. They are granted with the idea of return in some form. (Burling 1962)

This extends to acts of kindness. Individuals make choices over who they are kind to, and the other qualities of their kind acts.

Many definitions of kindness emphasize that, in common with altruism, kind acts are undertaken without expectation of reciprocity. This implies that the rewards to being kind are internal or indirect, rather than the direct result of an exchange. Consistent with this implication, Carter (2010) found that “kinder people actually live longer, healthier lives”.

People may not expect strict reciprocity for kind acts, but they are nonetheless unlikely to repeat kind acts that are met with hostility or studied indifference.

The kindness club?

Producers can choose who they are kind to, and under what circumstances. This makes kindness an excludable good (Samuelson 1954).

Kindness is non-rival in consumption, as one’s consumption of kindness does not subtract from anyone else’s enjoyment of (or ability to consume) kindness (Musgrave 1957).

Excludable, non-rival goods are known as club goods. Research into club goods has emphasised goods with economies of scale in production and/or consumption. Such goods are suited to collective action or institutions, hence clubs (Buchanan 1965).

Kindness, however, has limited economies of scale in production and no obvious economies of scale in consumption. And clubs seem ill-suited to the individualised production and consumption of kind acts. In practice, kindness better described as excludable and rival, that is a private good.

The quality of kindness

You got to try a little kindness

Yes, show a little kindness

Just shine your light for everyone to see (Sapaugh & Auston 1970)

Signaling theory (Spence 1973) tells us that when purchasers find it hard to determine quality, sellers with a higher quality product look for ways to “signal” that quality. However, a signal is not useful should sellers with low quality products fake the signal. Signals that are credible are typically those that come at some cost to the signaler, and that cost is observable by purchasers.

The recipients of kindness face a similar problem in distinguishing the quality of kindness: does an act reflect deep caring, or is it just a cheap fake? If the kindness involves a good or service with a market price, then recipients and observers can estimate its cost to the producer.

But what does quality mean when there is no market price? I think the key is personalization.

Kind adjective … that temper or disposition which delights in contributing to the happiness of others, which is exercised cheerfully in gratifying their wishes, supplying their wants or alleviating their distresses (Webster 1828)

This definition clearly emphasizes the recipient’s wishes, wants and distresses. Personalizing the kind act requires both empathy and information collection on the part of the producer. These factors cannot be cheaply faked, so act as a credible signal of quality.

Can’t buy me love … but can you buy kindness?

Tell me that you want the kind of things

That money just can't buy

I don't care too much for money

Money can't buy me love

While not widely known as economists, McCartney and Lennon (1964) clearly understood that love can neither be bought nor sold for money. Love must be freely given, as negotiations over a price will undermine its credibility.

Kindness shares this attribute with love — the nature of transaction fundamentally changes if it’s in exchange for money.

That said, an act of kindness does not carry the same risks as a declaration of love. In contrast to unrequited love, unrequited kindness does not appear to be a psychological, sociological or economic problem. Producers can experiment with low-cost kind acts, making higher cost acts conditional on a positive (or at least neutral) response.

Asymmetric information

When I ask you to be nice

You say

You've gotta be cruel to be kind

Lowe and Gomm (1979) point towards a well-known economic phenomenon: asymmetric information. Alice knows something that, should Bob hear of it, will make him unhappy or angry. So, it would be cruel for her to tell Bob. But Alice also believes the information has merit good characteristics (Musgrave 1957) — that is, it is in Bob’s interests to receive that information. Accordingly, it would be kind to tell Bob. This situation could also be viewed as a time inconsistency problem, resulting from a misalignment of Bob’s short-term and long-term preferences.

Strategic kindness

No war and anger was ever won

Put out the fire before igniting

Next time you're fighting

Please, kill 'em with kindness (Gomez 2016)

Economists love a game. Gomez advocates kindness as a game strategy, which appears applicable to the Prisoners’ dilemma (PD) game (Poundstone 1993). PD is a useful analogue for many real-world situations, including climate change, cartel behaviour and wars.

In a variant of PD where players knew each other’s reputation, cooperative behaviour emerged more quickly (Binglin & Yang 2010).

Say player 1 knows that player 2 has a reputation for kindness. If player 1 is kind, they can go straight to the cooperative equilibrium. If, however, they are unkind, they can exploit player 2 by consistently choosing uncooperative behaviour. So, a reputation for kindness is two-fold: it both invites exploitation, and raises the likelihood of finding socially optimal outcomes.

Measuring kindness

Not everything can be measured. Writing more than a century ago, economist Alfred Marshall recognized that actions

due to a feeling of duty and love of one’s neighbour, cannot be classed, reduced to law and measured; and it is for this reason, and not because they are not based on self-interest, that the machinery of economics cannot be brought to bear on them. (Marshall 1966)

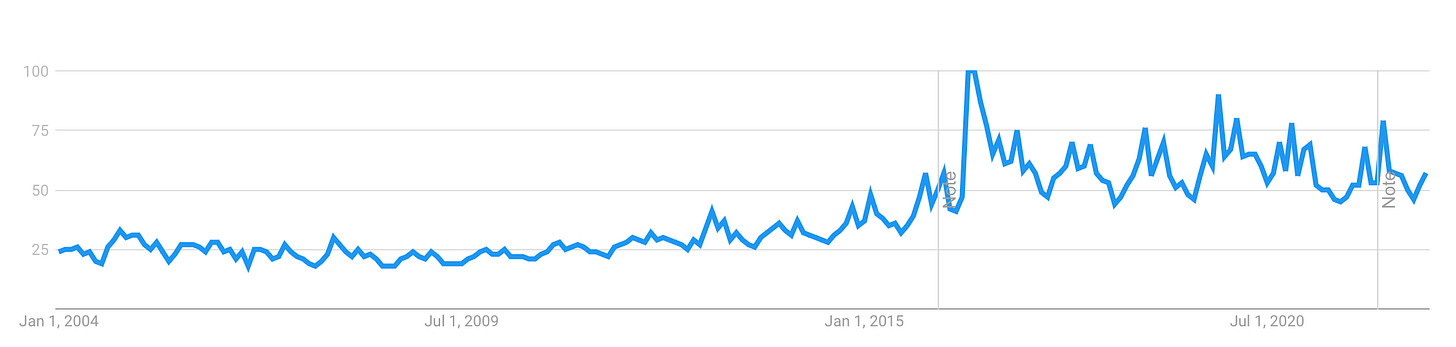

That said, even the great Marshall did not foresee a digital age with an omniscient Google. Web searches for “kindness” have trending upwards over recent years (Figure 1).

It’s all in a name

What should the field be called? The obvious choices are the kindness economy, kindness economics, and the economics of kindness.

The kindness economy (Portas 2021) “is a new value system where in order to thrive businesses must understand the fundamental role they play in the fabric of our lives” (How To Academy 2020). Value systems are normative rather than positivist, and an economy is more traditionally defined as an aggregate of voluntary trade and exchanges between those able to trade and exchange, not a value system that imposes conditions on thriving. This unhelpful precedent argues against kindness economy.

Kindness economics and economics of kindness appear to be synonyms. This is borne out by some examples: trade economics is, in practice, the economics of trade. Ditto for agriculture, energy, wellbeing, etc. But this equivalence is not universal — Doughnut Economics (Raworth 2017) is surprisingly scant on the economics of doughnuts. That counter-example favours economics of kindness over its near synonym.

Academia respects squatter’s rights. Those who name or first describe a new field get to choose names. I see no reason to revise Ardern’s (2019) nomenclature — the economics of kindness.

Conclusion

Kindness, despite being apparently divorced from the world of money, measurement, transactions and exchange, is amenable to the conceptual tools of economics. Some, necessarily preliminary, findings:

Kindness is individually produced, and its quality is determined by the degree to which it matches the preferences and needs of its recipient. It is, at least at higher quality levels, expensive to produce. Producers can thus be expected to economise on its production and/or expect some rewards.

Kindness is an excludable good, and non-rival in consumption. It thus fits the criteria for a club good. That said, it appears poorly suited to club production and consumption, so is better considered a private good.

A reputation for kindness is a two-edged sword. It both invites exploitation, and raises the likelihood of finding socially optimal outcomes.

Given the newness of the field, my analysis relies on some unconventional sources. These sources, my analysis, and its conclusions may prove controversial. That is not a problem in itself — controversy drives research, research drives publications, publications drive citations, and citations boost reputations in the strange world that economists inhabit. So be kind to the author, and kick off some controversy.

References

Ardern, J. (2019). Opinion: An economics of kindness. Beehive.govt.nz.

Bentham, Jeremy (1780). Value of a Lot of Pleasure or Pain, How to be Measured. pp.26–29 in An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. London: T. Payne and Sons. eText.

Bloom, N., Jones, C. I., Van Reenen, J., & Webb, M. (2020). Are ideas getting harder to find? American Economic Review, 110(4), 1104-44.

Buchanan, James M. (1965). An Economic Theory of Clubs, in Economica, New Series, Vol. 32, No. 125, pp. 1–14.

Burling, Robbins (1962) Maximization Theories and the Study of Economic Anthropology. Wiley Online Library.

Carter, Christine (2010). What We Get When We Give. February 18. Greater Good Magazine [website].

Easterlin, Richard A. (1974). Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? in Paul A. David & Melvin W. Reder (eds.) Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honour of Moses Abramovitz, New York: Academic Press, Inc.

Fire, Michael, & Guestrin, Carlos (2019). Over-optimization of academic publishing metrics: observing Goodhart’s Law in action. GigaScience, 8, 2019, 1–20.

Gomez, Selena (2016). Kill Em with Kindness [song]. Interscope.

Gong, Binglin, & Yang, Chun-Lei (2010). Reputation and Cooperation: An Experiment on Prisoner’s Dilemma with Second-Order Information.

Herbert, Anne (1982). Practice random kindness and senseless acts of beauty [placemat]. Sausalito, California.

How To Academy (2021). Mary Portas - How to Thrive in the New Kindness Economy [website].

Lowe, Nick & Gomm, Ian (1979). Cruel to be kind [song]. Columbia Records.

Marshall, Alfred (1966 [1920]), Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan.

McCartney, Paul & Lennon, John (1964). Can’t buy me love [song]. Parlophone Records.

Musgrave, Richard A. (1957). A Multiple Theory of Budget Determination, FinanzArchiv, New Series 25(1), pp. 33–43.

Oxford English Dictionary (2022). Oxford English Dictionary Online [website].

Portas, Mary (2021). Rebuild: How to thrive in the new Kindness Economy. Bantam Press.

Poundstone, William (1993). Prisoner's Dilemma. New York: Anchor.

Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist. Vermont: White River Junction.

Roberts, Russ (n.d.). Charity. In David R. Henderson (ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, Econlib.

Samuelson, Paul (1954). The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 36 (4): 387–389. doi:10.2307/1925895.

Sapaugh, Curt, & Austin, Bobby (1969). Try a little kindness [song], Performed by Glen Campbell. Capitol.

Spence, Michael (1973). Job Market Signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 87 (3): 355–374. doi:10.2307/1882010

Webster, Noah (1828). American Dictionary of the English Language. [Accessed online at https://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/Kind.]

Wikipedia contributors (2022, September 27). Seven virtues. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 00:42, October 23, 2022.

Richardson, Martin (1998). A Significant Heuristic Example of Erroneous Policy: the Determinants of Growth. Asymmetric Information, 2, July.

Entries as published must be 2250 words or less, including all tables, references, headings etc. They should contain at least 1, but no more than 5, photos and figures.

For more inspiration check out Yeh, Robert et al. (2018) Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma when jumping from aircraft: randomized controlled trial, BMJ 2018;363:k5094; and Lim, Megan S.C., Hellard, Margaret E., & Aitken, Campbell K. (2005) The case of the disappearing teaspoons: longitudinal cohort study of the displacement of teaspoons in an Australian research institute, BMJ 2005;331:1498–500.

As I will be screening and sub-editing entries, Mary has ruled me ineligible for the prize.

I was chuffed to see the inverted ewe in my inbox on the weekend! (I still like it, even though a friend once suggested the data would be more clear in a baa graph.) That note of mine actually had a quasi-serious point, as a reductio critique of some terrible work in growth empirics that was kicking around at the time. As I recall, Ted Sieper had prepared for Treasury an excellent gutting of the method behind this work, and I had discussed it in an Honours class at Otago. One of the students asked something to the effect of, 'couldn't that methodology be applied to anything (rather than the government expenditure to which it had been applied); say, sheep numbers?' So it started with a student's question and Nancy Devlin very graciously accepted it for AI, perhaps the perfect outlet. (The data used were all genuine, by the way, so the results are even more persuasive!) Anyway, thanks for the reminder of it, Dave.

Great idea Dave! I’d like to write about the productivity impacts of working from home in New Zealand, drawing on the small number of studies I’m familiar with. Some people had inadequate home working arrangements at the beginning of the pandemic (Making, Du, 2020) but Hazno, Kidd et al reported in 2021 that some workers can be very productive WFH. A recent survey of New Zealand firms shows they are either positive or equivocal about the longer run impacts of WFH on their bottom lines (Shelby, Wright & Dunno, 2022). Unfortunately, some people will be experiencing the effects of “long Covid” – the term coined by Weary in 2020 – but as Couch, Poot, Ayto found in an exhaustive study in 2022, many people just suffer from poor motivation when they’re at home, so I probably won’t get round to it!