Discussions about tax policy are often heated, but rarely conclusive. Most people can agree that someone needs to be taxed more heavily — as long as that someone is “someone other than me”! And top of the list of someone-other-than-me’s is “the rich”. They can, after all, afford it. They have miniscule voting power, as there are relatively few of them. And further, if Netflix series and social media are any guide, there is nothing much to like about the rich, even if we remain fascinated by their lifestyles.

Eat the rich!

The oft-quoted (but, I hope, rarely acted on) political slogan Eat the rich! got me thinking about an analogy between taxing the rich and, of all things, fisheries management.

Maximum yield from a fishery

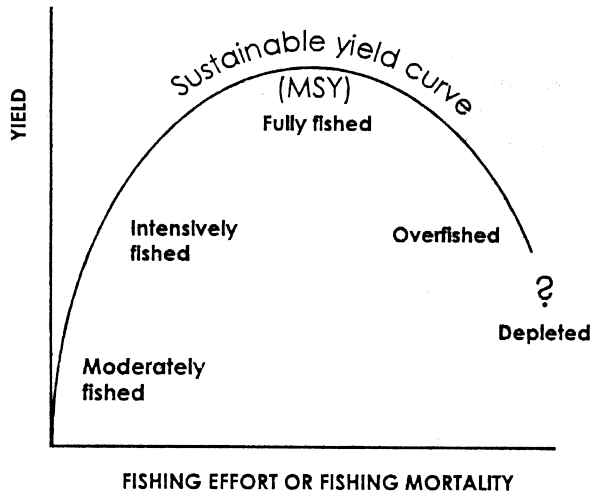

A central concept in fisheries management is maximum sustainable yield (MSY). It’s a pretty simple idea. If you fish too hard, the fish population can’t renew itself quickly enough, so the population collapses (as did the Atlantic northwest cod fishery). And so does the “yield” — the quantity of fish extracted for humans to eat. Fish too little, however, and while fish population is fine you aren’t feeding many humans. Somewhere in the middle is a sweet spot — the MSY — with a sustainable fish population and a high yield.

While both fishers and conservationists can agree about the desirability of sustainable fishing, getting agreement on catch limits is hard. Calculating the MSY is tricky. Concerned about possible population collapse, conservationists prefer to err to left-hand side. Fishers, concerned about stranded fishing assets and not trusting conservationists, typically advocate higher limits, arguing that any errors to the right-hand side today can be repaired later.

Maximum yield from a tax base

Take the MSY graph above, change fish yield to revenue, and fishing effort to tax rate, and you get something that looks remarkable like a Laffer curve.

The Laffer curve is named after economist Arthur Laffer, who famously sketched the curve on a napkin to illustrate his point. "Laffer curve” became a hot-button political term in 1970s US after some conservative politicians used it argue that their planned cuts to tax rates would increase government revenue. Short answer: it didn’t.

But it wasn’t Laffer that was wrong. The problem was that politicians had assumed that the then current tax rate was on the right-hand side of the maximum sustainable revenue (MSR) point. It turned out that the rate was actually to the left-hand side, so revenue fell in response to a lower tax rate.

Dodging the tax collector

It’s pretty easy to see why a fish population collapses if you extract too many and eat them. Fishing also creates strong selection pressure in an evolutionary sense, so fish change their behaviour to avoid being caught.1 Behavioural change reduces the size of the fishable population, further reducing the MSY.

Taxpayers are not actually eaten (even if some complain as if they were!). Taxpayers do, however, change their behaviour in response to tax-rate changes. It is these behavioural changes that drive down total revenue on the right-hand side of the Laffer curve. They include:

out migration, as the rich typically have many options to move themselves and/or their tax residency to other countries;

increased tax avoidance activity;

reduced incentives to earn taxable income, typically resulting in working fewer hours, lower investment in human capital, and less entrepreneurial activity; and

increased collection and enforcement costs, which reduce net revenue.

Such behaviours are undesirable, from a revenue-raising perspective.

The rich are a scarce resource

NZ is a small place. Damien Grant thinks we should be celebrating the rich, not hitting them with more taxes, pointing out that just 311 families are paying $1bn of tax a year. Sustainable management of such a small stock is important — NZ can ill afford to lose too many of them. Ideally, we want to increase the stock, with both home-grown and imported varieties.

Sin taxes are distinct from revenue taxes

Taxes can be broadly split into sin taxes and revenue taxes. While both raise money for the government, they differ in some fundamental ways:

Sin taxes are those imposed with the primary purpose of changing behaviour. Want to reduce smoking? Tax cigarettes. Likewise alcohol, greenhouse emissions, nitrate pollution, etc. The right tax rate is the one that encourages the optimum level of behaviour change, not the one the raises the most money.

Revenue taxes are those imposed with the primary purpose of collecting money. The right tax rate is the one that raises the optimum amount of money in the long run, typically involving a low level of behavioural change.

Slogans like “eat the rich” or “tax the rich” conflate an apparent sin of being rich with the desirability of a tax system that raises more revenue from those most able to pay.

The sustainable fisheries analogy gives us a more useful way to think about taxing the wealthy. It asks us to concentrate on one question: how do we maximise tax revenue, without threatening the size and health of the stock?

By Dave Heatley

Fish don’t change their individual behaviour in response to fishing, unless near misses are common, and fish are capable are learning from them. A more realistic explanation of behavioural change is that genetic traits that make a fish more likely to be caught are less likely to be passed on to the next generation, while behavioural traits in surviving fish do get passed on.

This is obviously "tongue in cheek". But I would just make two comments.

First, the issue about the wealthy is that they are often able to order their affairs in such a way as to ensure that the effective rate of tax they pay is low. I think it is Warren Buffett who said he was amazed to see that he paid a rate of tax less than his secretary. The fact that NZ's wealthy families pay so much tax (at least according to a well-known contrarian columnist) is that they are, well, very wealthy and this tells you less about the duress they are under than the state of inequality - and maybe also our over-reliance on income tax as a source of revenue. And they help fund elections (at least for one side of politics!).

Second, I know this is all in humour, but I think the use of the term "sin" tax is pejorative. Surely, from an economist's point of view, wouldn't it be better to regard them as externalities that inflict costs on the tax payer, and this is a way of recouping those costs - be it lung cancer, alcohol-induced trauma and other outcomes, accidents (hence, ACC)? You could add environmental despoilation and pollution to the list of "sins"!

Also, as I see it, a capital gains tax is not necessarily about raising revenue (although it may do some of that) but also, or even more, about modifying behaviour (a "sin" tax?). One of the reasons we have such an outsize property debt burden and housing prices that are (relatively speaking) internationally leading is that our lack of a CGT (and other supportive policy settings) favour investment in property over the productive economy. So, with any luck, and the appropriate policy settings, we might start to get more investment in the productive economy than in the property market.

Hi Dave, I like your analogy with fish. You note that behavioural changes in fish that avoid being caught may be passed on to other fish. Similarly, as tax rates rise and some of the rich change their behaviour to 'avoid being caught' such as by engaging in tax evasion or avoidance, they will pass on this acquired knowledge to their heirs and friends. This transmitted knowledge might then continue to be acted upon even if tax rates revert to the earlier lower level at which these behavioural changes had not yet been triggered. So, raising tax rates (even if temporarily) exerts a ratchet effect upon the behavioural changes. Thus, the amount of tax collected depends not just upon the current tax rates but earlier rates as well.