In the sixth NZAE Member Survey1 we asked questions related to three fringe2 (i.e. non-mainstream) concepts gaining popularity among some economists: Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics, Mariana Mazzucato’s mission-based economics, and the circular economy.

Takeaway — a strong divergence of views

One takeaway from this survey is that academic economists disagreed that these concepts are improving economic policy analyses, and that these concepts should be taught as part of the economics curriculum at all. In the words of one respondent: “As an economics lecturer, I am loathe to introduce non-science based concepts into the curriculum. (This is the same reason I/we are reluctant to teach Modern Monetary Theory - another popular set of non-scientific econ "meme" theories)”.

However, the exact opposite is true for government economists. While the survey is non-representative for either group, this suggests an important and potentially dangerous divergence of views about the usefulness of these fringe concepts.

“As an economics lecturer, I am loathe to introduce non-science based concepts into the curriculum” — respondent

Survey details

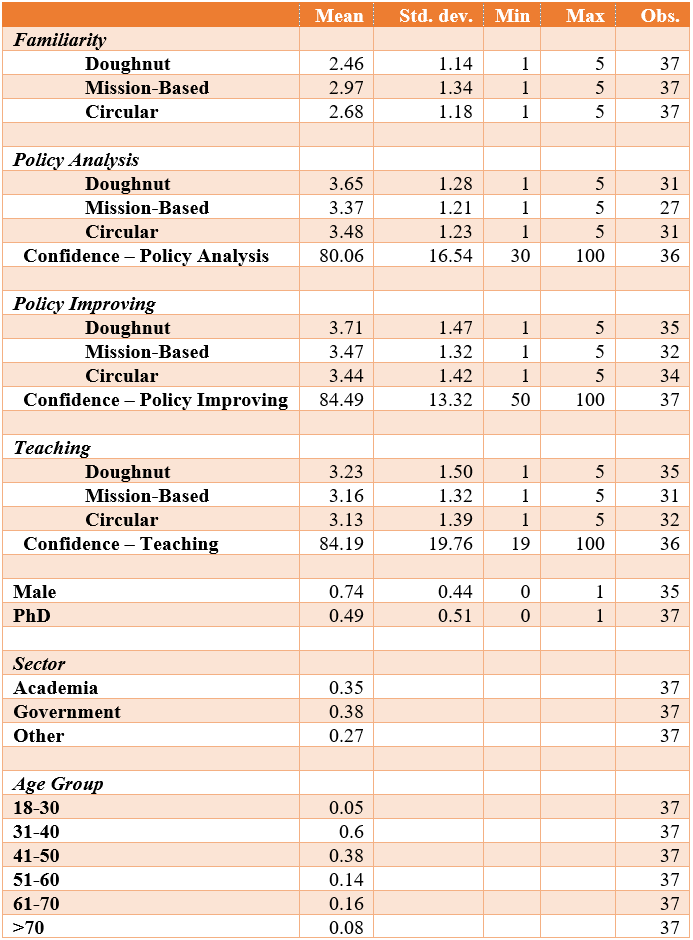

The survey was circulated amongst NZAE members on Monday, May 8 and was open for 7 days. During that time, 37 respondents answered the survey. 74% of respondents were male, and 49% held a PhD. 73% of respondents worked in academia or in the government. The 41-50 age group was best represented (38%).3

Familiarity with concepts

To set the stage, question 1 asked the level of familiarity (5-point Likert scale) of the respondent with each of the concepts.4 We found that at least 81% of respondents are somewhat familiar with the concept of doughnut economics, 62% with mission-based economics, and 73% with the circular economy. This varied greatly between academia and government respondents. For all three concepts, respondents working in the government were more familiar. Overall, this should indicate that respondents were credibly able to answer the next questions.

Policy analysis

Q2. To the extent that [each of Doughnut Economics, Mission-based economics & the Circular Economy] has been incorporated into economic policy analysis by Ministries and Agencies, it has improved the quality of that analysis.

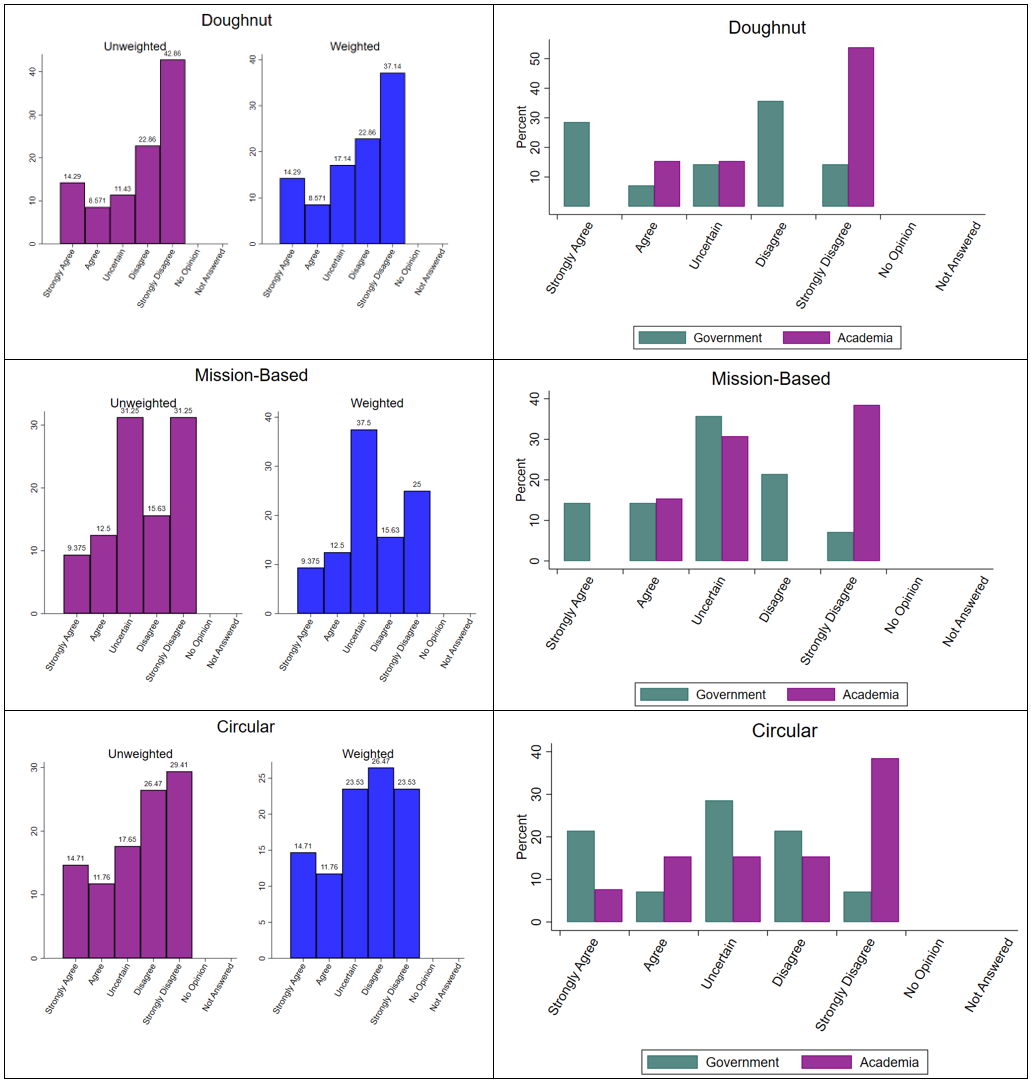

In question 2, we asked whether the quality of economic policy analysis is higher when these concepts are included.5 Most respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed (54%) that doughnut economics improves economic analyses — only 19% agreed or strongly agreed. For mission-based economics, 40% disagreed or strongly disagreed, while 25% agreed or strongly agreed. Likewise, for the circular economy, 52% at least disagreed that the concept improves economic analysis, while 22% at least agreed. Disaggregating the data shows a level of disagreement between academia and the government sector so far unprecedented in our surveys. In short, most academics disagree that these concepts improve economic analysis, while government respondents agree or are uncertain.

Improving policy analysis

Q3. Economic policy would be improved by placing greater weight on [each of Doughnut Economics, Mission-based economics & the Circular Economy], even if it meant less analyst time and capability was available for other types of analysis.

Question 3 took this further and asked whether the quality of an economic policy analysis would be improved if these concepts were given a higher weight.6 A large majority (65%) at least disagreed when referring to doughnut economics, with only 22% at least agreeing. For mission-based economics, 46% at least disagreed (21% at least agreed) and for the circular economy, 55% at least disagreed (26% at least agreed). Again, we find dramatic differences between government and academia. In short: academic economist disagreed, while government economists agreed that giving a higher weight to these concepts would improve policy analysis.

Teaching

Q4. Independent of being in or out of fashion in Wellington policymaking, [each of Doughnut Economics, Mission-based economics & the Circular Economy] would be a useful addition to the core syllabus in economics.

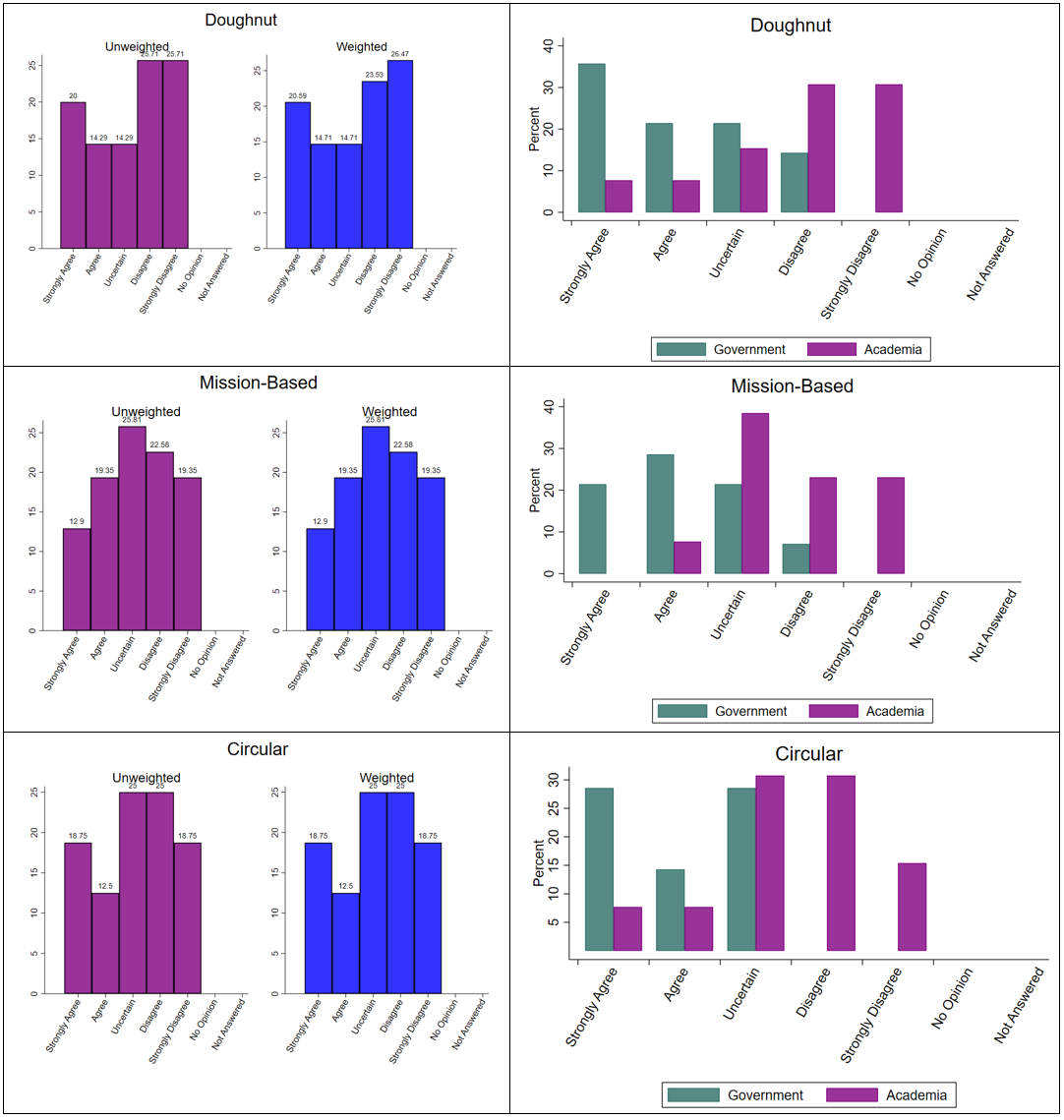

The final question asked whether these concepts should be taught as part of the core syllabus in economics.7 For doughnut economics, 51% at least disagreed that it should be taught and 34% at least agreed. For mission-based economics, 41% at least disagreed with 31% at least agreed. Finally, for the circular economy we find that 43% at least disagreed with 31% at least agreed. We again find substantial differences between academia and government respondents: academics tend to disagree, while government economists tend to agree that these concepts should be taught.

“I think there's a useful element in Mazzucato's work (state capability matters for economic development / innovation) that could fit into a broader course on development economics or economics of innovation. But Mazzucato's whole theoretical critique doesn't stand up very well” — respondent

Weighting

The survey also elicits the confidence in the answer to each of the three questions. This information can be used to weight the responses. We present the unweighted (raw) and weighted survey responses below.8 We found little divergence between the weighted and unweighted results. The results reported above are unweighted.

Commentary

The economics discipline evolves — too slowly for some, too fast for others. New concepts, frameworks, ideas and challenges continually appear at its fringes, each with advocates and detractors — many of them passionate. Some of these concepts prove themselves to be both valid and useful, and these get absorbed over time into the core discipline. Many, perhaps most, fade away, of interest only to the discipline’s historians. While an concept remains part of the fringe, it is difficult, perhaps impossible, to predict its eventual fate.

This NZAE member survey has revealed the greatest divergence of views of the 6 conducted to date. This suggests that the three concepts surveyed — doughnut economics, mission-based economics and the circular economy — are currently in this existential limbo.

Academic and government economists are polarised as to the validity and utility of these concepts. One possibility is that they have strong appeal because they describe real problems, but annoy others because the solutions they prescribe are unsatisfactory on one or more dimensions. What are your thoughts?

These regular surveys ask NZAE members about topical New Zealand issues. We share the results with members and other AI subscribers, within a month of the survey closing. You can read the reports on previous surveys here: #1 labour market issues, #2 rent control, high-skilled migration, & MMT, #3 NZ emissions trading scheme (ETS), #4 taming inflation, and #5 academic and government NZAE members divided on greed inflation.

Editor’s note. I struggled over whether “fringe” was the best choice of word here. I was concerned that it might read as pejorative. The analogy of a “fringe festival” (e.g. arts, music) persuaded me to retain it. A fringe festival is where all the new, interesting and experimental stuff can be found. Some brilliant, some awful …

Without an optimal weighting approach, we weight the survey responses as follows. We first compute the mean confidence for each question. Then, for each respondent, we compute the absolute distance from the confidence mean weighted by the confidence standard deviation. If the response is above (below) the midpoint (i.e., disagree and strongly disagree) and the confidence is above mean confidence, we add (subtract) the weighting factor. If the response is above (below) the midpoint (i.e., disagree and strongly disagree) and the confidence is below mean confidence, we subtract (add) the weighting factor. We also use a multiple this weighting factor by 0.49 to smooth the weighting.