Your average wombat is probably smarter🍋

World Wombat Day gave me the excuse to review the new Apple Intelligence

Just about everything has its own international day, even wombats. Last Wednesday was World Wombat Day.

Days are in limited supply, with a world limit of 366, so 22 October was also Leave a Review Day.1 I thought I’d combine the two themes, and use wombats to review a pre-release copy of “Apple Intelligence”, a collection of artificial intelligence (AI) features that will debut on iPhones, iPads and Macs in the coming weeks.2

Apple have been slow off the mark in adding AI features to its products. It is, however, the world’s top consumer electronics company. While it is often not the first to introduce shiny new features, its trademark design consistency and polish means that its implementations typically end up being admired and copied by its competitors. With all the hype, and not a little disillusionment, around AI at the moment, I was keen to see a mature implementation of AI in consumer products.

Find me a wombat

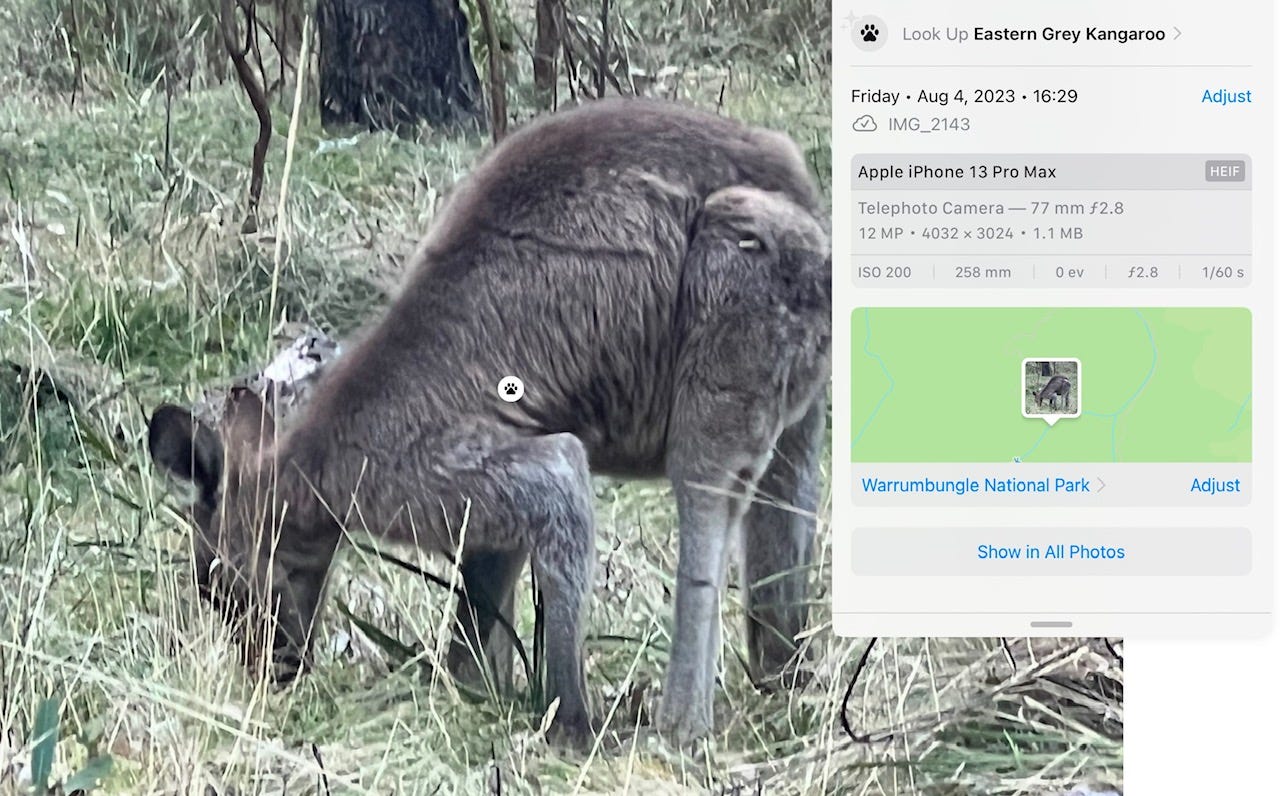

Apple’s photo search is impressively fast. It took no time at all to find a wombat photo (above) from my 26,000 item gallery. Not so impressively, it also tells me that kangaroos are wombats.

At least both kangaroos and wombats are Australian marsupials. As were the koalas, wallabies and quokkas in my “wombat” photo gallery. But that doesn’t explain the mammals and birds masquerading as wombats: black bears, squirrels and hoary marmots from Canada, and fur seals, elephant seals, rock wrens, and kea from New Zealand.

AI excels at common cases, fails with less common ones

Machine learning is hungry for data. Large-language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are pre-trained with trillions of tokens of data. (A token is roughly equivalent to four characters of text, or 1/30th of an image).3 Even when trained on such huge datasets, LLMs have problems with edge cases — situations that are absent or appear rarely in the training data.

A design feature of Apple Intelligence is that it runs locally on your device rather than in the cloud. This reduces privacy risks but comes with a downside — models that can run locally are trained on smaller datasets than cloud-based models.

Smaller training datasets means that local models are more likely to suffer from edge-case effects. That may explain what is going on here. A photo search on my phone for kangaroo returns only kangaroos. As it does for kea. Wombats are just less popular, and the web data available for training reflects that.4

A collection of small models invites inconsistency

Rather than one super-charged LLM to perform every task, Apple seems to have gone for specialised models for specific tasks. So while the “photo search” model thinks that the photo below contains a wombat, the animal “lookup” model correctly identifies it as an eastern grey kangaroo.

If the information from one model is not available to other models, then inconsistencies such as this can be expected.

AI summaries are always confident but not always right

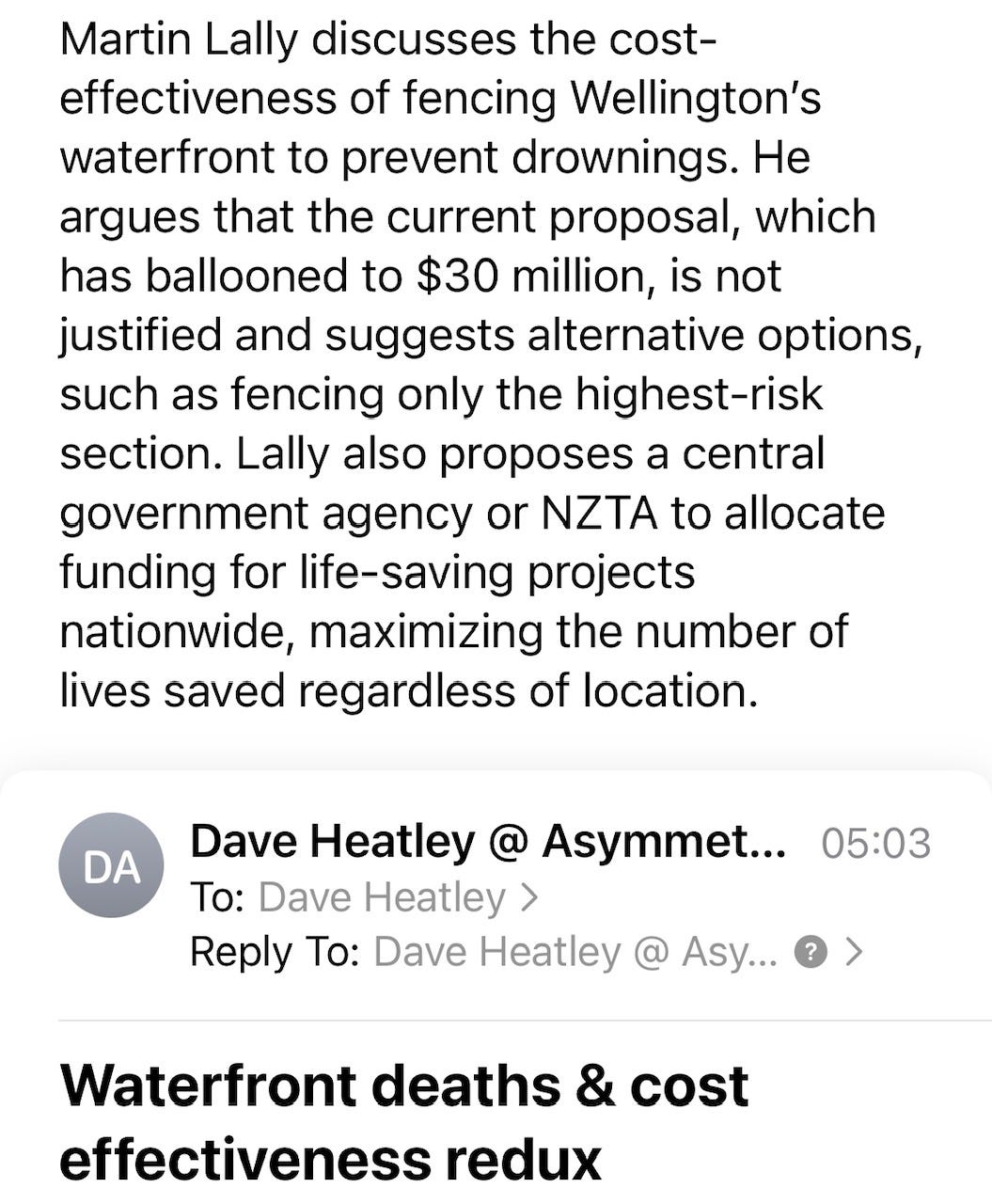

Apple Intelligence has powerful summarisation features. When asked to summarise the email containing Martin Lally’s post Waterfront deaths & cost effectiveness redux, it displayed:

Which is perfect. Except for one detail — Martin argued that the proposal was justified, even at the inflated price of $30 million. And getting that detail wrong makes the whole summary misleading.

For notifications and the inbox list, my iPhone now displays a short AI-generated summary of the email, rather than its tructated text. Which in many cases is the much more useful option. But sometimes the summaries are just plain wrong.

This creates an interesting dilemma. Say you are sending a crucial email, one that you do not want the receiver to misinterpret. You now run the risk that the receiver will see an AI-generated summary instead of the text you wrote. Should you send it to yourself first to check out the AI summary, just to see what the receiver will see? But what if you don’t know which device or operating system the recipient is running? You’re stumped.

A seemingly benign AI feature, designed to make life simpler, might just end up making it more complex.

Priority spam is worse than regular spam

Apple Intelligence reads my incoming mail to identify and tag “priority” items, and displays these at the top of my inbox. It helpfully did so for an email urging me to “take urgent action now” and to transfer money to some well-deserving person. I know they were well deserving because the email’s subject line declared it to be “*** SPAM ***”.

No doubt the next update of Apple Intelligence will recognise clearly labelled spam and deal with it appropriately. But the world’s spammers will experiment, looking to see what they can craft to get Apple’s implied endorsement as a “priority” email. An arms race will ensure, no doubt. Will we be better off? I suspect not.

But some features are cool

Apple’s voice recognition just keeps getting better. And the voicemail transcription feature is a useful and amazing piece of engineering. Two technical problems that stymied computer scientists for many decades — voice synthesis and recognition — must now be considered solved.

Your average wombat is probably smarter

Apple produce polished and capable consumer devices on which many of us rely. In my assessment, Apple Intelligence makes them even more capable but less trustworthy. There is no question that AI-written summaries, for example, can save time. But for anything really important, Apple users will now need to manually check that their device’s “intelligence” is not misleading them. Is that trade-off worthwhile?

Wombats are not known for being smart. But that doesn’t mean they are stupid. Evolution is unforgiving; confusing a wombat with an elephant seal is likely to be fatal. Lacking a similar mechanism, I fear that artificial intelligence still lags behind the biological sort.

By Dave Heatley

October 22nd is also International Caps Lock Day. I assure readers that no caps lock key was harmed while writing this post.

Apple Intelligence is a collection of features that will be available for iPhones (16 and 15 Pro models), and for iPads (with an M series processor). It will be delivered via an operating system update (iOS/iPadOS version 18.1). Delivery is expected in November 2024 for US customers, and in December 2024 for New Zealand customers. This post is based on my experiences with a release candidate of the US version of iOS/iPadOS 18.1. Apple Intelligence is also coming for Macs; but I have not tried that out.

Villibos et al. (2024). Will we run out of data? Limits of LLM scaling based on human-generated data.

As I don’t know of a way of finding out how many photos of a particular animal are on the web, I tried simple text searches as a proxy for commonness. My Google searches for “kangaroo”, “kea” and “wombat” returned 141 million, 79 million, and 29 million results respectively. This is consistent with my preconceptions that wombats are the least well-known of the three.